Belzoni’s watercolours of Seti I’s tomb at the Bristol Museum

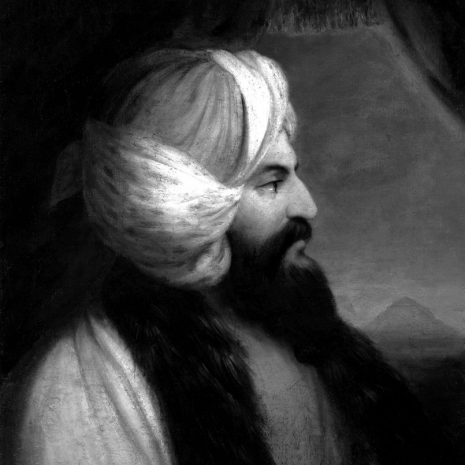

Born in Padua, Italy, in 1778, Giovanni Battista Belzoni led a colourful life. He studied hydraulic engineering in Rome when he was young, but then moved to the Netherlands and worked as a barber. He subsequently joined a circus in England, performing as a strongman, where he’d carry up to 12 people at a time across the circus floor (he stood in at 6′ 7″; impressive, even by today’s standards). An obvious career path, wouldn’t you agree!

In 1812, Belzoni and his wife Sara found themselves in Egypt, working on a hydraulic engineering project.

This trip to Egypt turned into an extended stay, after Henry Salt employed him to move a colossal statue from the Ramesseum to the British Museum.

This then led on to a multitude of archaeological work in Egypt, which included clearing Abu Simbel of its huge sand drifts, exploring many ancient sites and, in 1817, discovering the tomb of the pharaoh Seti I in the Valley of the Kings (KV17).

Belzoni spent some three years recording the texts and artwork in the tomb, and his watercolours found their way to the Bristol Museum in 1900.

These paintings are of particular importance now, as the walls of KV17 have, unfortunately, degraded considerably over the years (although some of this degradation happened at the hands of Belzoni himself, when he took wet squeezes of some of the walls!).

A selection of his watercolours have been on temporary display during the summer months of 2013 as part of the museum’s Pharaoh Reborn display, and I was fortunate enough to be able to go and see them whilst visiting family in the south-west of England.

The paintings are truly beautiful, and valuable artworks in themselves, so I wanted to share some of my photographs of them here with you. Unfortunately, due to the watercolours being protected by glass, there are a few reflections visible, but I do hope it doesn’t spoil your enjoyment of the pictures.

All of the photos will open into larger images when you click on them.

(Edit: Although the exhibition credits Belzoni himself for all the watercolours, it has since come to my attention that Belzoni’s colleague Alessandro Ricci assisted with the survey of the tomb, and worked on many of the pieces you see here. So, all credit where it’s due! Many thanks to Dyan Hilton for passing this information on.)

Before we get started …

… it’d be rude not to mention Tutan-Gromit. He’s been greeting visitors at the entrance to the museum as a part of the Gromit Unleashed project, which has been raising money for the Bristol Children’s Hospital.

During 2013, there are 80 Gromits across the city, all decorated in weird and wonderful ways. My favourite is, of course, Tutan-Gromit (as I’m sure you’ll agree!).

For those not familiar, Gromit is the canine companion of Wallace, a pair of animated characters created by Nick Park’s Bristol-based Aardman Studios, who have now become great British icons. Aardman also made the Creature Comforts animations and movies such as Chicken Run and Early Man.

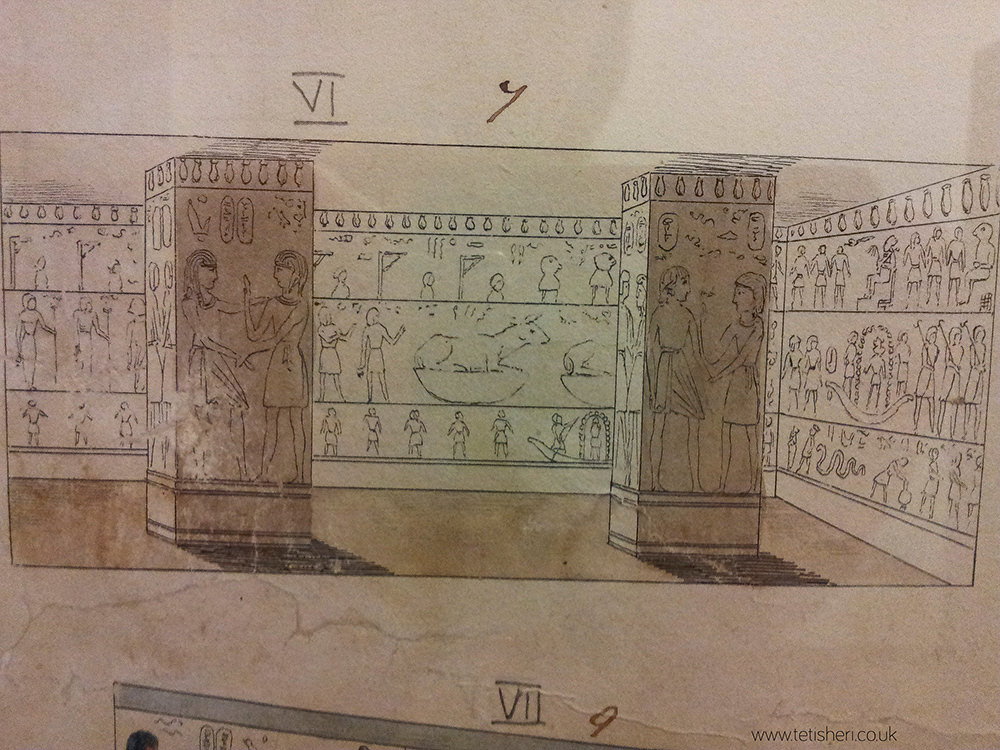

Tomb plan

One of the first watercolours in the gallery was Belzoni’s plan of the tomb. Unfortunately, my photograph of the whole picture didn’t come out very well, but there’s an image of it on the New York Public Library’s website.

The two pictures I’ve included above are of the burial chamber and one of the pillared rooms. The actual size of them (the paintings, not the rooms themselves!) is only a few inches wide, so the detail Belzoni’s included is quite impressive. I would imagine some of his paintbrushes were only a few bristles thick to get such fine lines.

Nekhbet

This painting is of the vulture goddess Nekhbet, who guarded the entrance to Seti’s tomb. The inscription above her wings contains two of Seti’s names. On the left (reading left to right), it reads:

Son of Re, Lord of Apparitions, Mery-en-ptah, like Re

The text on the right, reading right to left, says:

The Good God, Lord of the Two Lands, Men-maat-re, given life

The two names translate as ‘Beloved of Ptah’ and ‘The Maat of Re Endures’.

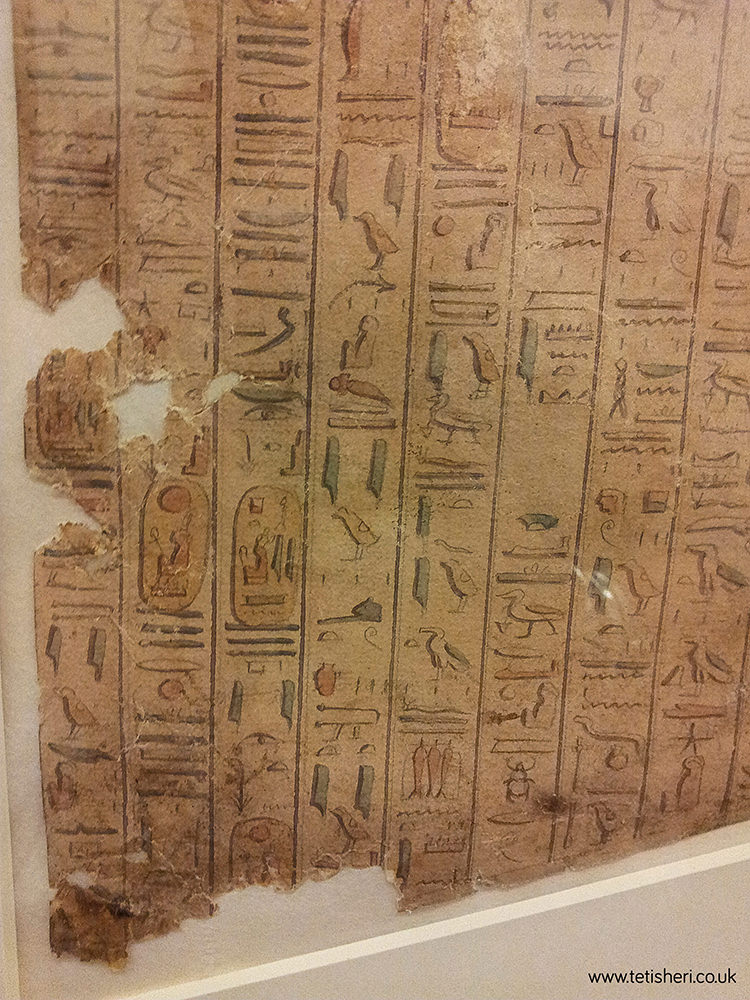

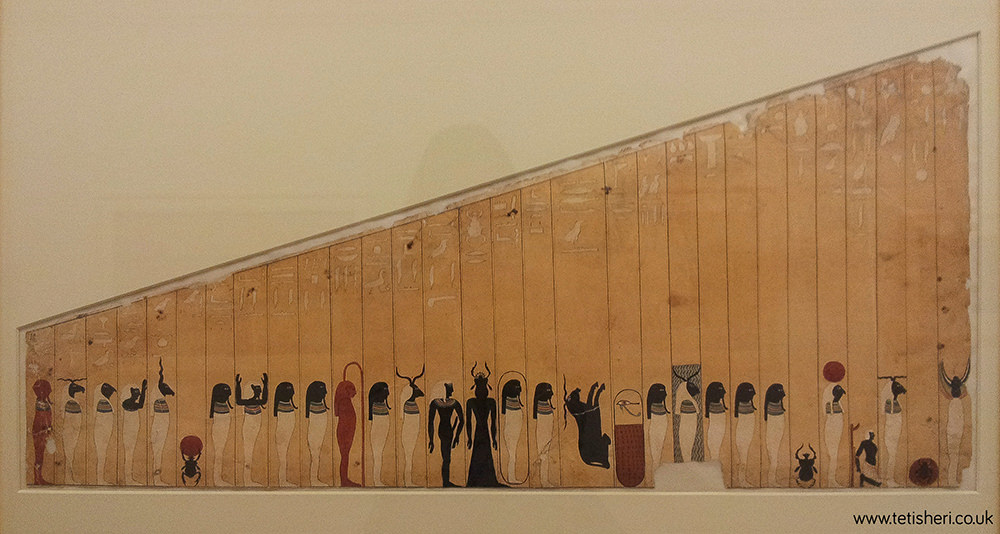

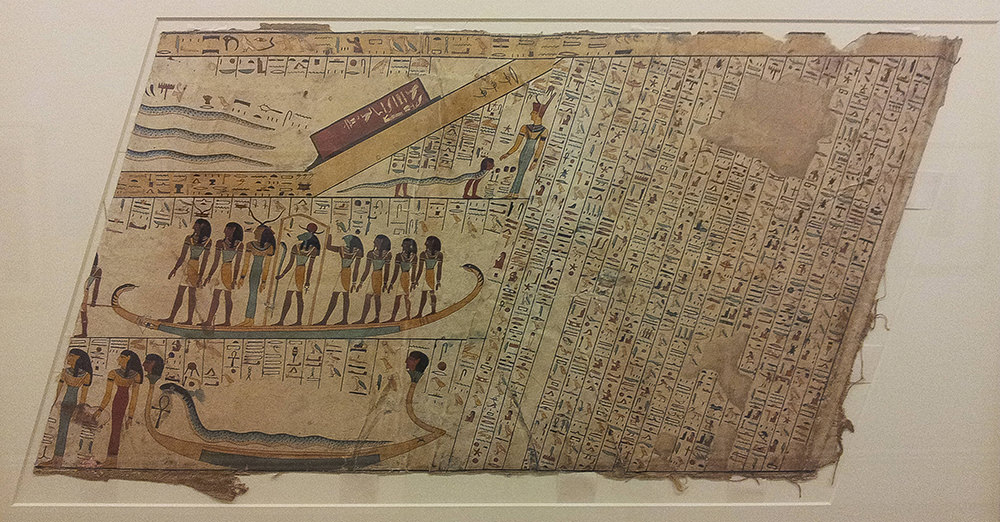

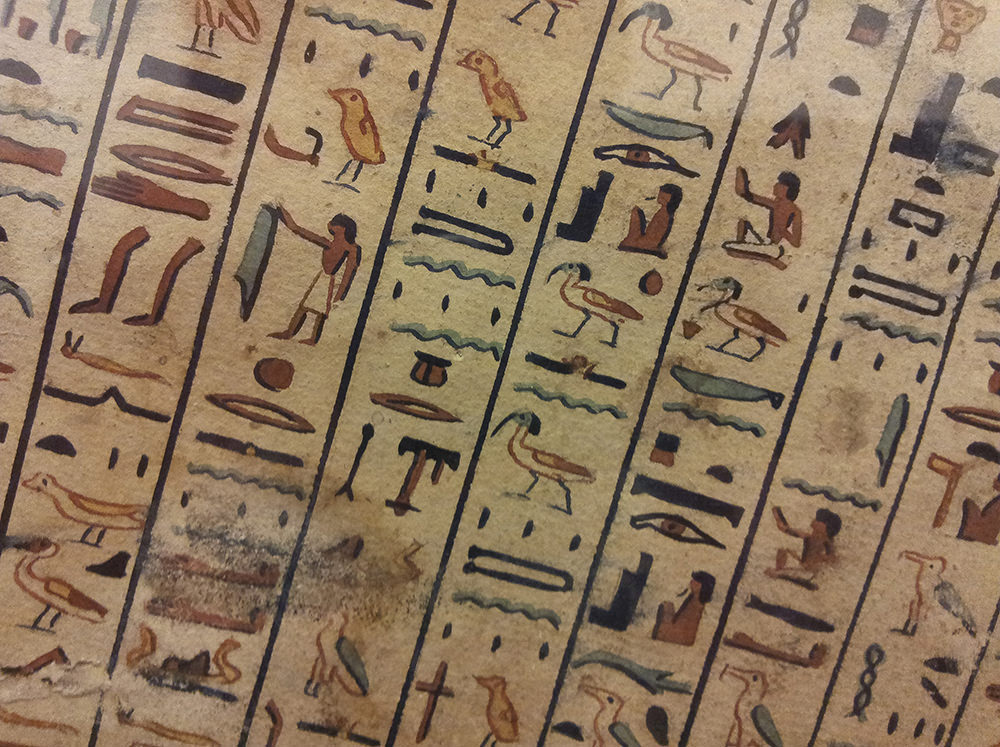

The Litany of Re

The Litany of Re was a New Kingdom funerary text, reserved for the pharaoh and a handful of only the most favoured top-level dignitaries. According to Wikipedia:

It is a two-part composition that in the first part invokes the sun, Ra, in 75 different forms. The second part is a series of prayers in which the pharaoh assumes parts of nature and deities, but mostly of the sun god.

It was found mostly on tomb walls, in the corridors leading down into the tomb (hence the slanting shape of Belzoni’s paintings).

The Litany included the invocation of the 75 forms of Re, some of which are shown in the third picture below.

In the second picture, you can see the detail that Belzoni included; it was a complete recording of the texts. I can’t imagine how many hours it took. But, this was what we had to do to record tombs before the advent of cameras.

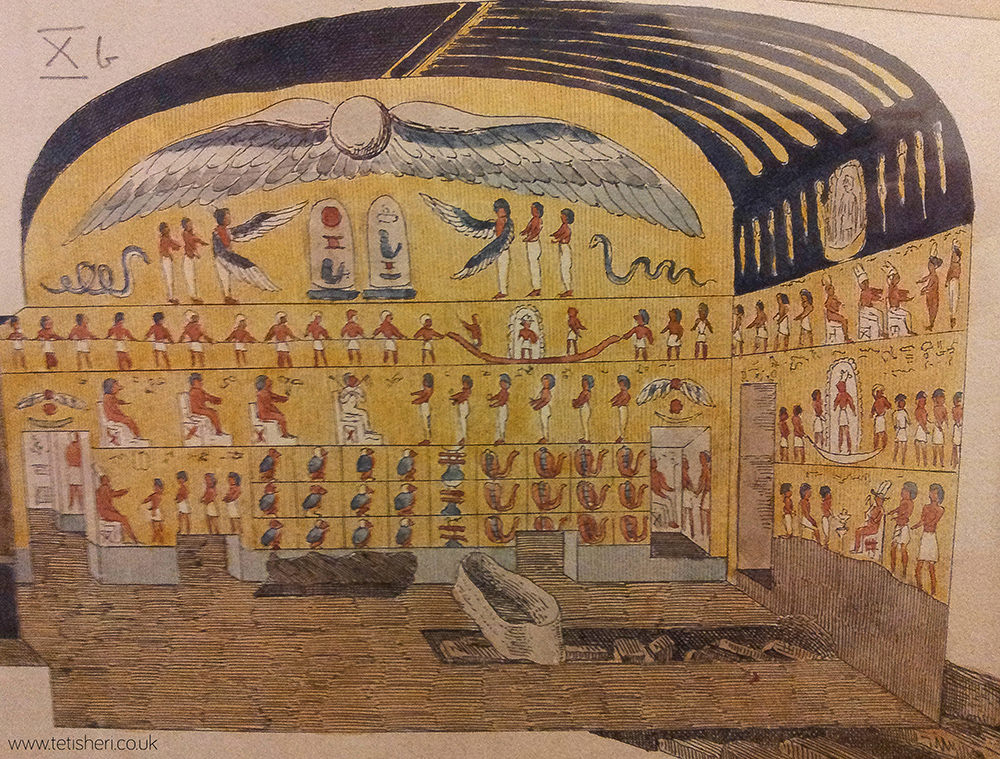

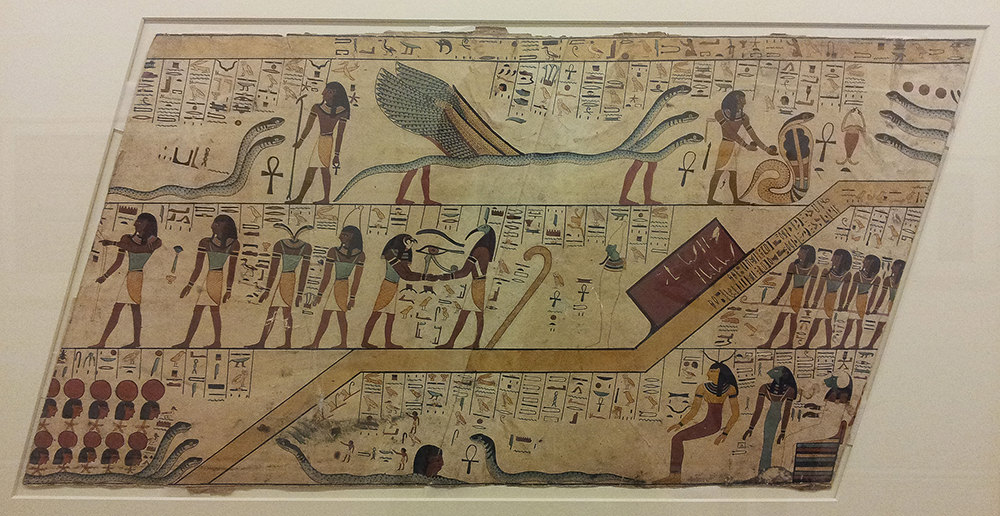

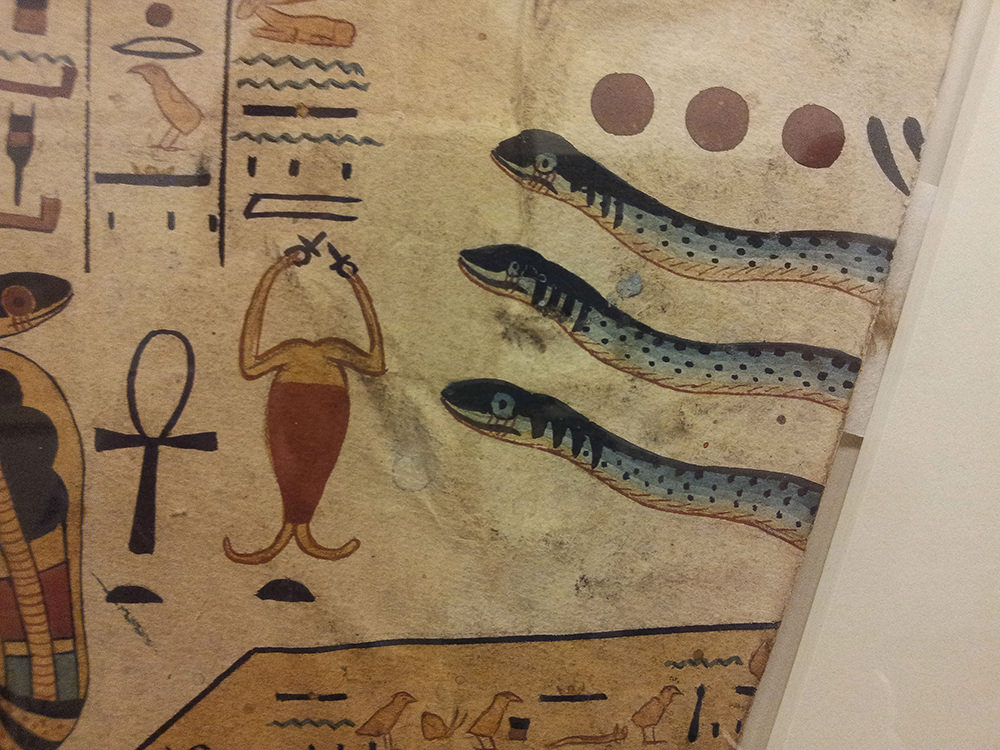

Fourth hour of the Amduat

The Amduat (or, ‘that which is in the underworld’) was another New Kingdom funerary text, reserved for the pharaoh and the lucky chosen few.

It detailed Re’s nighttime journey through the underworld, which was divided into twelve hours.

In each hour, Re (and, therefore, the deceased king) faced challenges and myriad gods and demons. The text provided spells and incantations, as well as the names of these underworld beings for the king to utter, so he could then call upon the gods and defeat the demons.

The fourth hour was called ‘The Land of Sokar’, a desert, where Re’s boat is transformed into a serpent, and is confronted by malevolent snakes, complete with legs and wings, who would have to be pacified before Re could pass through the land.

The details I’ve included here are of, formerly, the top right corner of the first watercolour; I love the three snakes – the colours and the markings. Beautiful! And, latterly, of the hieroglyphs on the second painting; the detail Belzoni has gone to is quite marvellous.

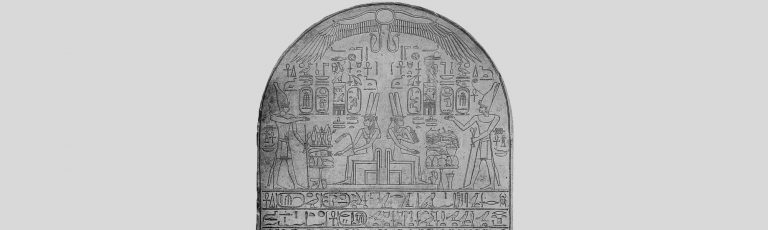

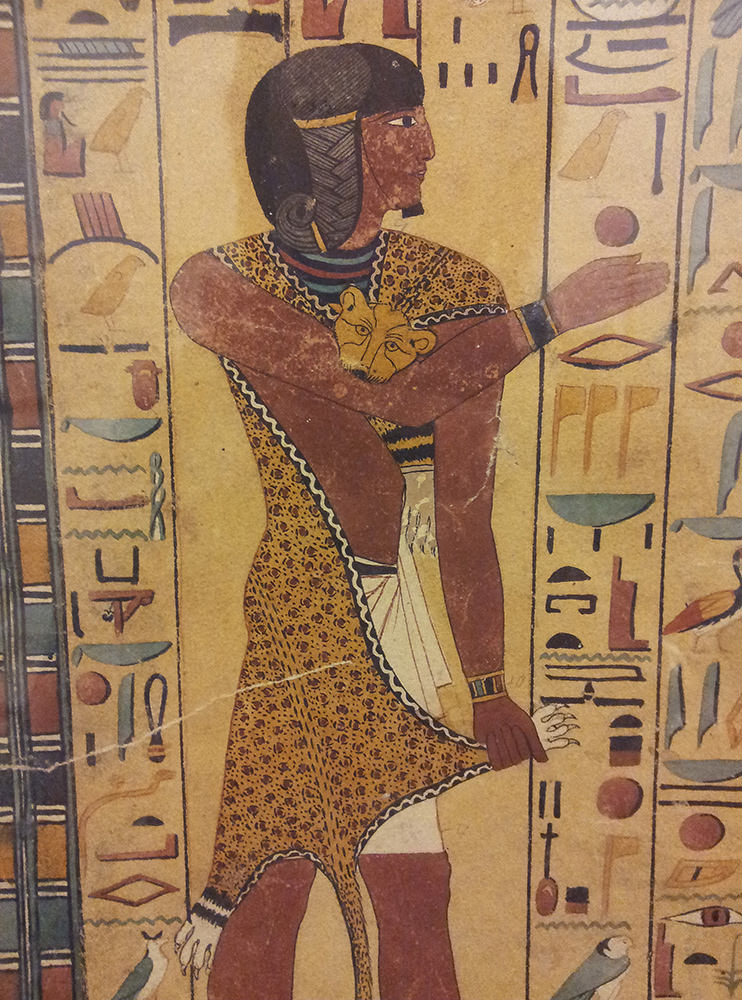

Opening of the mouth ceremony

This plate details part of the ‘Opening of the Mouth’ funerary ritual. Along the top register, stands a statue of Seti being put through various purification rituals.

The second picture is a detail of the first, of a bullock being slaughtered as part of the funeral. I was particularly drawn to it because of the intricate detail on both the priests’ leopard skin and the bullock’s hide.

Doorway with inscription

This painting is of a doorway bearing the same two names of Seti as shown in the painting of Nekhbet, above (each cartouche is included here twice).

(Apologies for the large reflection across the middle; there was a fluorescent light directly above, and I just couldn’t quite manage to avoid it!)

Of particular interest on this painting, is the handwritten inscription at the bottom of the left-hand-side of the picture, which reads:

Copy from the original drawing

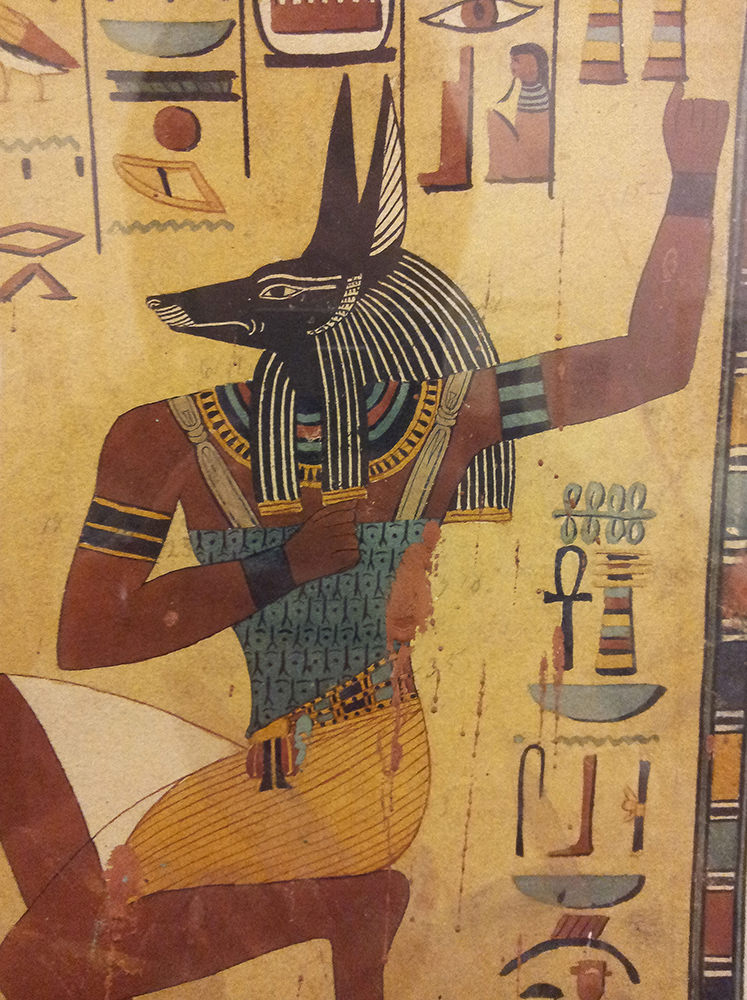

Pillar decoration

These two pictures are details from pillar decorations. The first is an Iunmutef priest, identifiable by his leopard skin and ‘sidelock of youth’ hair.

The jackal is not, as you might think, Anubis; it is, in fact, a Soul of Nekhen. The Souls of Nekhen were considered ancestors of the king, Nekhen being the Egyptian name for the ancient city of Hierakonpolis.

Again, I was drawn to these because of the beauty of the detail: the priest’s leopard skin and the head of the jackal, in particular.

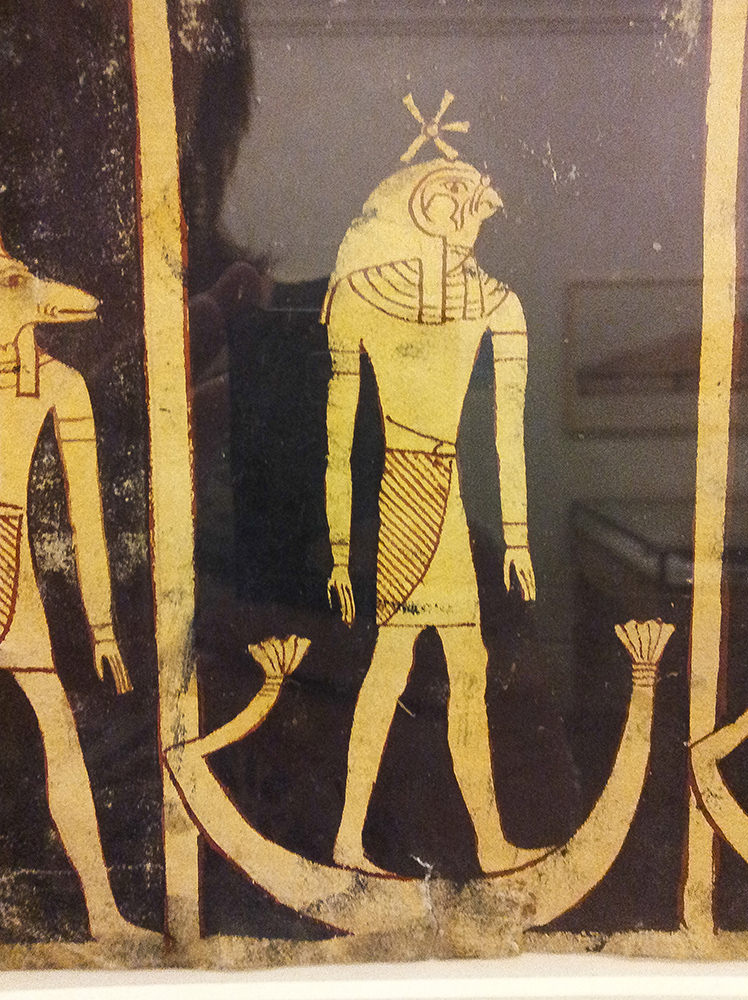

Astronomical ceiling

One of my favourite things! Astronomical ceilings are a whole topic within themselves, but if you’re not familiar, they’re depictions of the night sky found on tomb ceilings from the New Kingdom onwards.

Here, you can see just a small part of the astronomical ceiling from Seti’s tomb; it shows several constellations depicted as gods, as you can see from the stars above their heads (and, on three of them, their full names).

Unfortunately, apart from a very few constellations, it’s proved almost impossible so far to match up the ancient Egyptian constellations and their stars with the stars as we know them today.

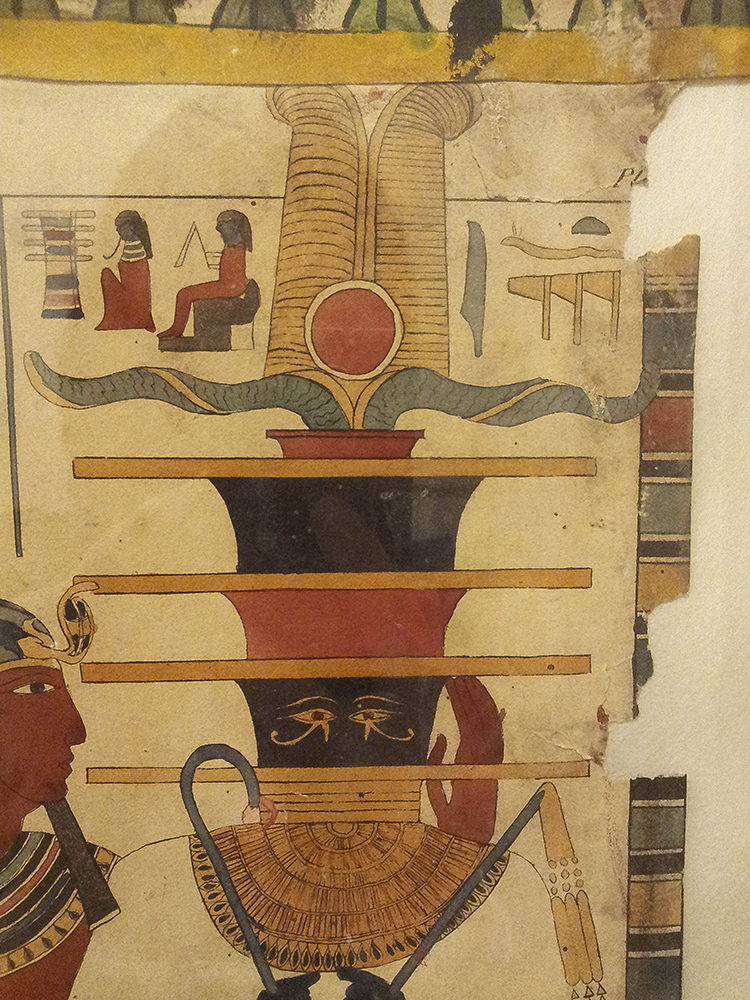

Seti before the djed-headed Osiris

The Egyptians certainly weren’t lacking in imagination, as well demonstrated here. This rather curious-looking god is in fact Osiris, with a djed for a head (I’m sure there’s a rap in there somewhere …).

But, why would they do this? Well, the djed symbolised stability and the rebirth of Osiris (and therefore the king), making it a rather desirable image to include in a tomb.

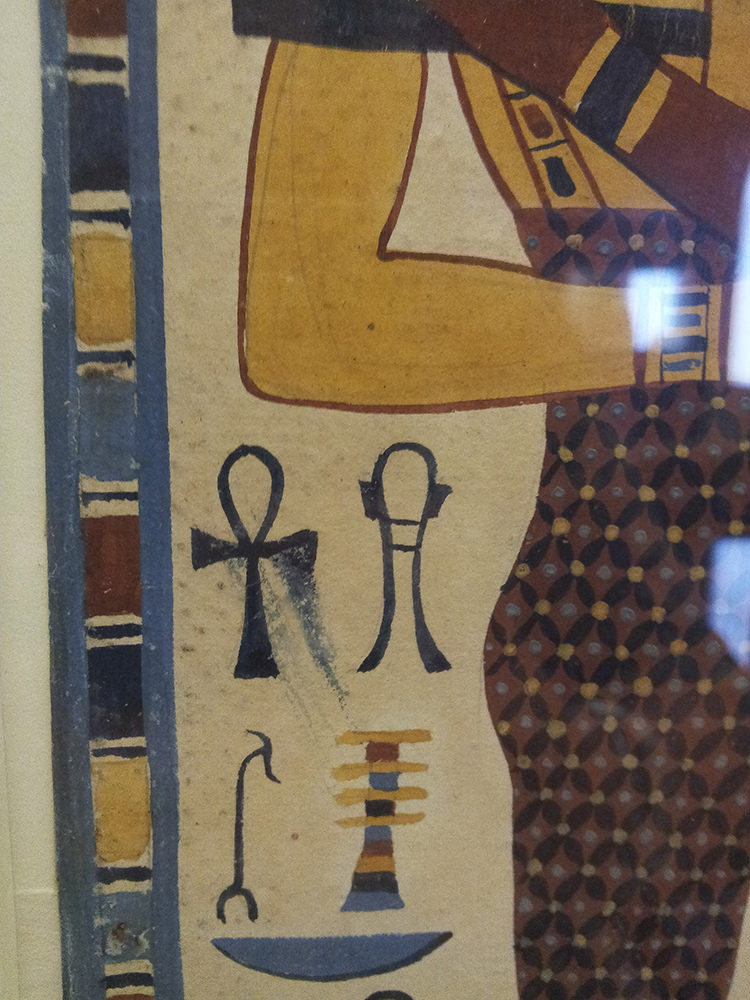

The downside of watercolour paints

This photo is a detail from Belzoni’s painting of Seti standing before Hathor. The main reason I’ve included it was that, as well as the lovely big smudge on the ankh, demonstrating the vulnerability of this method of tomb recording, I love that you can see Belzoni’s original pencil marks on the arm of Hathor. It makes me think of those unfinished tombs where you can see the ancient artisan’s outline sketches on the wall.

And I do think the detail on Hathor’s dress is quite beautiful.

And finally, a rather special grave

Not part of the Bristol Museum, but this grave does deserve a special mention. I visited it as part of my Egyptological activities on my holiday – it’s at the church of St Mary the Virgin, in Henbury (north-west Bristol). The inscription you can see here reads:

Here lies the body of

Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards

Novelist and archaeologist

born in London on the 7th June 1831.

Died at Weston-Super-Mare on the 15th April 1892.Who by her writings and

her labours enriched the

thought and interests of her time.

Amelia Edwards was, of course, the founder of the Egypt Exploration Fund (now The Egypt Exploration Society), a crusader for the preservation and protection of Egyptian heritage, and wrote such classics as A Thousand Miles up the Nile.

Her grave is aptly fitted-out with an obelisk and a beautiful stone ankh.

The graveyard is full of wonderful old gravestones, many from the 18th century. If you do drop by, be sure to look out for the grave of Scipio Africanus (you won’t miss it!).

Further reading

- Belzoni on the Fitzwilliam site

- Belzoni on the Tour Egypt website

- Belzoni on Wikipedia

- Eric Hornung, The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife (New York, 1999), for more information about the funerary texts on the wall of KV17

- Nicholas Reeves and Richard H Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings (London 1996), for more about Belzoni (pp 56-60) and KV17 (pp136-139)

- Belzoni documentary: a few years ago, the BBC produced a series of dramatised documentaries about pioneering Egyptologists. You can watch the Belzoni episode, The Temple in the Sands, on YouTube here

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!