Photographing the coffin of Tasheriankh for Golden Mummies of Egypt

Warning: this post contains some photos of mummified human remains.

Have you ever wondered how a photographer goes about photographing a 2m-long ancient Egyptian coffin?

Do we stand the coffin up on end? Sometimes, I guess, if the coffin’s already standing this way. Not all coffins are robust enough to do this, though.

Do we stand on a step-ladder to look down over it? I dunno. Seems a little risky to me.

Do we hang from the ceiling, floating above it, camera in hand? Er, no.

So, how do we do it then?

Well, unsurprisingly, it depends. Personally, I can’t know how I’m going to photograph something so large until I know more about where I’m going to be photographing it.

Because there were several coffins and mummy covers to photograph for the Golden Mummies of Egypt exhibition, this was one of the first discussions curator Campbell Price and I had when we teamed up.

In this post:

Working out where to photograph large artefacts without a photography studio

Manchester Museum doesn’t have its own photography rooms, so right from the start, Campbell and I had to work out where I was going to photograph 100 artefacts, ranging from a 1cm-wide earring to 2m-long coffins.

We settled on a corner of the zoology stores for the small artefacts. For the coffins, however, we had to be practical. They’re big, and some are really quite delicate. One option was to set up in the conservation labs, which I didn’t want to do, because they have bright lights, people working in them and no blinds on the windows.

I was also a little unsure as to how I’d get high-up enough to get full-length shots of them. There’s a set of moving steps in there (like a beefy, wide stepladder), but the dyspraxic in me really didn’t like the idea of that.

I suggested the organics storeroom (where artefacts made of natural, degradable materials are stored) as an alternative. Not only was this where the coffins were being stored anyway – minimising the need for more museum staff to have to spend time bringing artefacts to me – it was ideal for my setup because:

- there are no windows to let daylight in

- there was no-one else working in there, so I could switch the main lights off and use my own, and – best of all –

- there’s a mezzanine level in the room

The mezzanine would be ideal for getting me up high-enough to get those sought-after full-length photos.

Of course, the organics stores wasn’t a perfect solution because it’s densely packed with artefacts. There are quite a few coffins stored in the area under the mezzanine, and there isn’t much space between the edge of the mezzanine and the wall, where more coffins are stored. There really isn’t much room for manoeuvre.

However, being able to get up high and having complete control over the lighting trumped not having much space. I can work in a tight space. I can’t (unfortunately) use the powers of levitation to hover up over a coffin to photograph it.

So, the stores it was.

Who was Tasheriankh?

Whilst there were several coffins and mummy covers to photograph for Golden Mummies of Egypt, one of the highlights of the exhibition was the coffin and mummy of a woman called Tasheriankh.

Tasheriankh (Ta-sheri-ankh, The Living Child) lived in Akhmim – a city just over 80 miles north-west of Luxor – during the early Ptolemaic period, around 300 BC. Sadly, she was only around the age of 20 when she died.

Tasheriankh was mummified and laid to rest in her wooden, anthropoid (human-/mummy-shaped) coffin, with a cartonnage (a mixture of linen and plaster) chest cover.

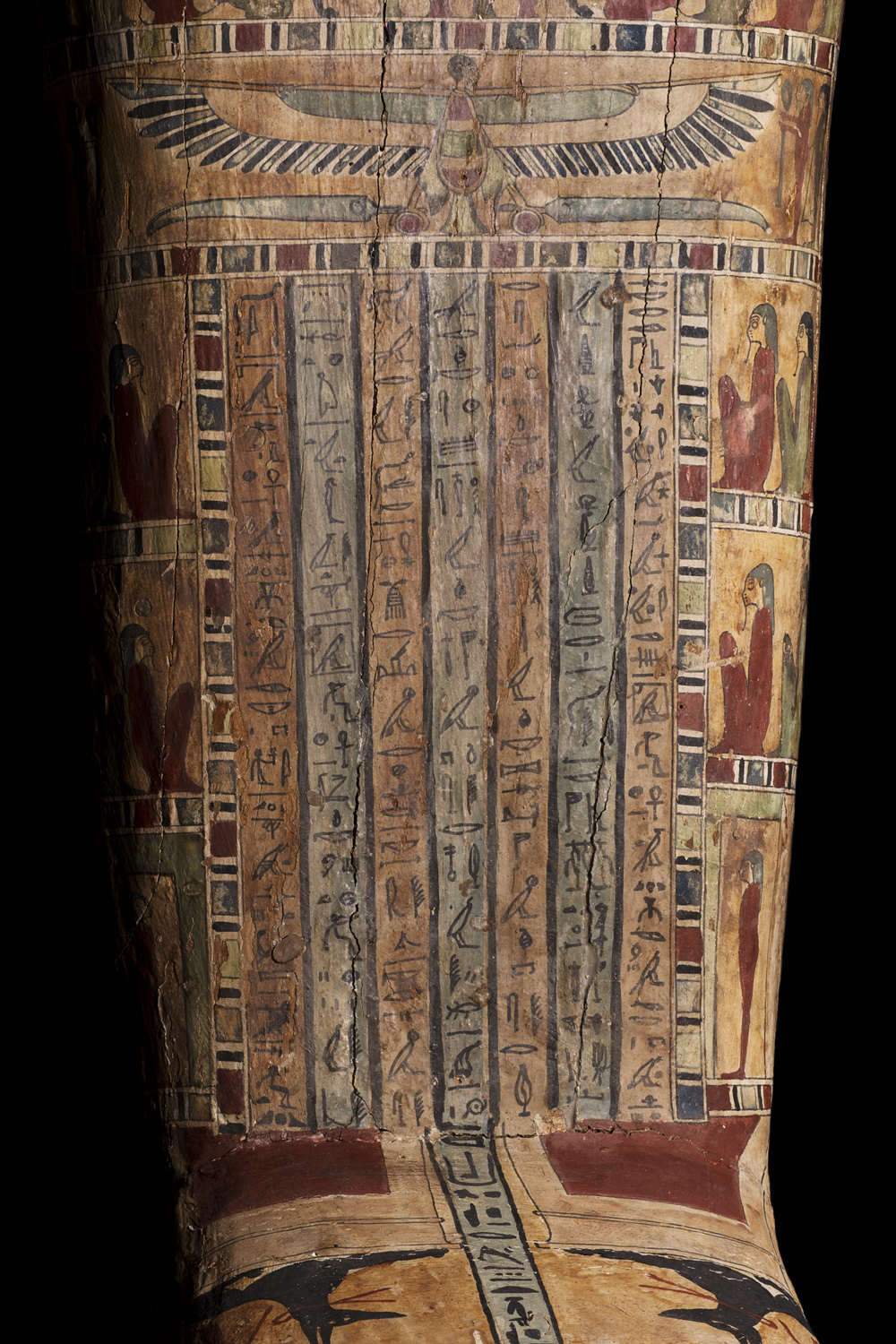

Both her coffin and cartonnage cover are heavily decorated with typical scenes of deities, embalming and hieroglyphic spells.

If you’d like to know more about Tasheriankh, Campbell Price wrote a piece about the Golden Mummies exhibition in issue #24 of Nile magazine, including a more detailed description of her, the symbology in the coffin decorations, and how she came to be in the collection at Manchester Museum.

What photographic equipment did I use?

If you’re not interested in the technical specs, just jump past this section to the next one.

However, for those of you who like the details:

I used a Fujifilm X-T2 camera using all three of my lenses (not all at the same time, mind): the XF 16mm, the XF 35mm and the XF 80mm macro.

I used two LED panel lights and a Manfrotto tripod with a geared head.

I used a remote shutter cable so I didn’t have to touch (and therefore judder) the camera when actually taking the photos, and a 3D spirit level so I could make sure my camera wasn’t sitting wonky.

Photographing Tasheriankh

Because Tasheriankh was a highlight piece, we wanted to photograph her in more detail than the other coffins. Not only did we want those straightforward full-length shots, we also wanted to pick out details of the painted decorations and texts on her coffin, so I spent around two days in total photographing her.

Which is just what I love to do.

It’s so much more fun – and meaningful – to be able to spend time with an artefact, photographing it several different ways, finding those little details and shapes and textures that you might miss when you’re piling through the objects as fast as you can.

And Tasheriankh’s coffin, as is the case with many Egyptian coffins, has every last millimetre of surface covered with images, with hieroglyphs and with gorgeous repeating patterns.

Whilst full of symbolism and beauty, these pieces can be overwhelming to look at, and details can get lost in the overall immense busyness of these pieces.

Taking the time to photograph the coffin from different angles and to pick out important and interesting details can help bring more meaning to these pieces for me and for you. It helps bring focus and clarity.

When I first photographed Tasheriankh, her funerary mask was being worked on by the conservators. Because we weren’t sure how long the conservators would need, we didn’t want to risk running out of time and not being able to photograph Tasheriankh properly, so we got on with the photography anyway. I started by photographing the outside of the coffin and her wrapped mummy in the base of the coffin.

I then got another session in right towards the end of my sessions there, once the conservators had finished the mask.

Photographing Tasheriankh from the mezzanine

Whilst I could, perhaps, have got full-length photos of Tasheriankh by standing the tripod next to her, I’d have had to have the legs extended so tall, I wouldn’t have been able to reach the camera controls without one of them pesky stepladders (!).

This is why the mezzanine was so useful.

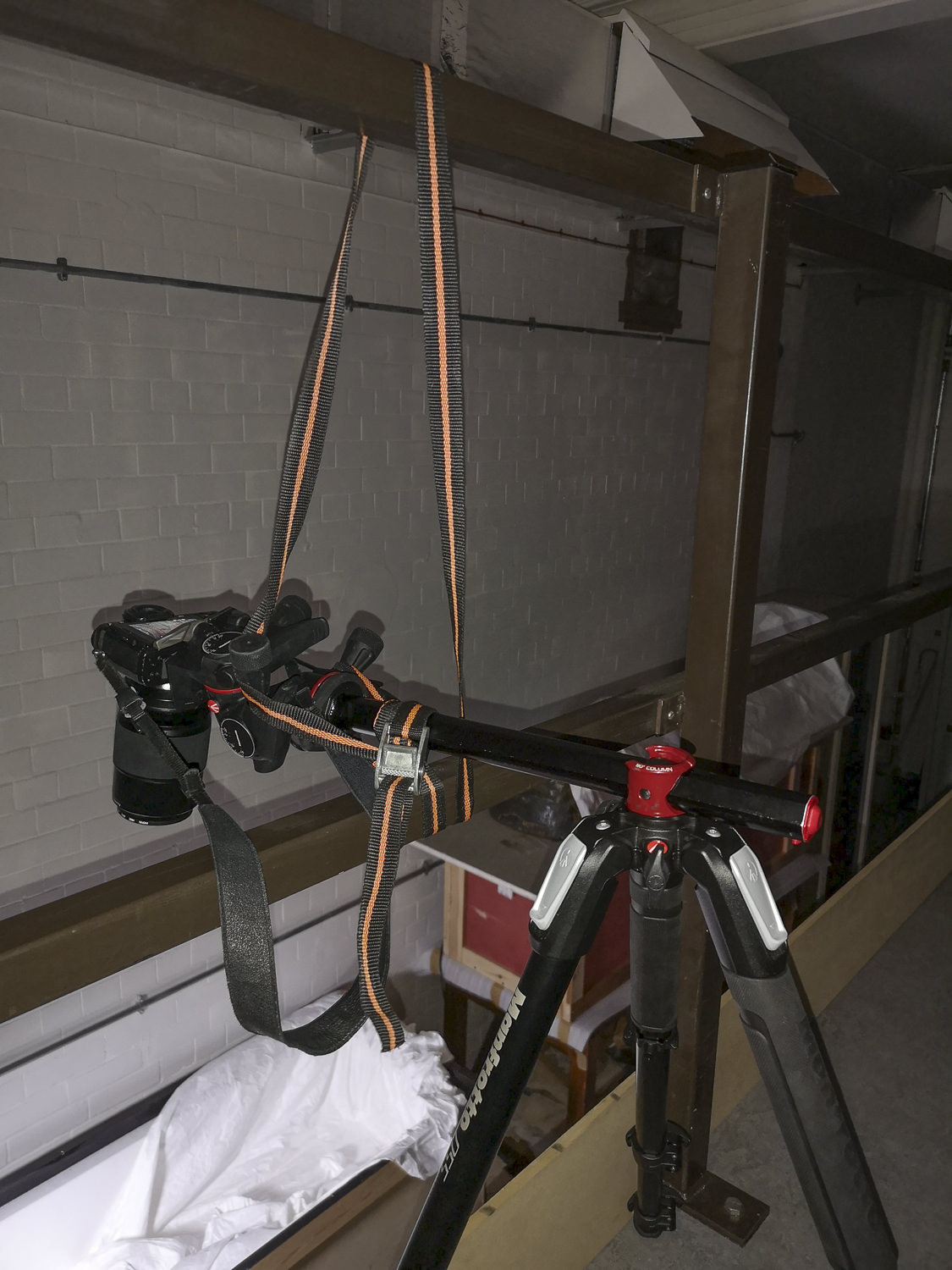

My tripod has a pole that comes up and out of the centre to lie at a 90°-angle to the legs, so I can have my camera looking downwards instead of forwards.

This meant that I could have my camera extended out over the edge of the mezzanine, looking down onto the coffin.

Doing this isn’t something I’d take lightly, however. Oh my goodness, no!

Not only is my expensive camera and lens hanging out over a 10ish-foot drop, having the camera set up this way creates an uneven distribution of weight on the tripod.

In other words, it could easily tip over the railings and onto the 2,500-year-old, irreplaceable coffin below.

So, what did I do? I lashed the tripod to the railings along the edge of the mezzanine using one of those strong weaved-canvas straps, which I’d borrowed from one of the lovely museum facilities guys (thanks Bob!).

I wound the strap back and forth around various bits of the tripod and the railings and made sure there was no slack in the strap so that the tripod was rock-solid. It was surprisingly time-consuming. It took me about as long to get the tripod securely strapped up as it did to set all the rest of my equipment up.

But, there are some things you just don’t skimp on …

From up here, I could use my 16mm and 35mm lenses to get the full-length shots, and my 80mm lens to get the detailed shots.

Securing the tripod wasn’t the only obstacle, however.

The other one was changing the positioning of the coffin in front of the camera to get different shots. It’s easy enough when it’s a small artefact on a table. I can just move artefact or camera (or both) to get where I need.

However, when it’s a 2m-long coffin and a tripod lashed to a railing, it’s a whole different ballgame.

I had two options open to me:

- Untie the tripod, move the camera, then retie the tripod

- Keep the camera in one place and move the coffin around beneath it

As the tying and untying of the tripod was time-consuming, and the coffin was on a wheeled trolley, the second option was the obvious one.

But, going down the mezzanine stairs to adjust the coffin then back up to check how it looked through the camera, potentially several times for each shot, was not really how I wanted to spend my day.

That’s where my camera app came in handy.

Fujfilm, like many camera manufacturers, have an app you can install on your phone, which connects your phone to your camera, enabling me to see what the camera sees on my phone screen. So I’d set the app running, take my phone down to the coffin, move the trolley around using the preview on the app to check it was in position, then go back up to the camera. Doing it this way meant I could get the shot lined up in one run of the stairs.

Here’s a screenshot I took from my phone of the app when I was lining Tasheriankh up for a photo.

(Yes, that’s me taking the screenshot. In the screenshot. #meta)

And these are some of the photos I took from up on the mezzanine:

Getting up-close with Tasheriankh

Not everything I wanted to do could be done from the mezzanine, however.

There were several details I wanted to capture that I either needed to get much closer up to, or were on sloped parts of the coffin I couldn’t see so well from above.

So I also spent some time down on the storeroom floor, up-close and personal with Tasheriankh.

This photography was much more straightforward. I could move the camera and lights around as I pleased (within the confines of the restricted space, of course), and I didn’t have to leave my camera to line the shots up.

I did, however, need to do more focus-stacking with the close-up shots, because focus falls away much more quickly when you’re close to your subject.

Some of my favourite details from the coffin are:

Getting creative with composition

I also took the opportunity to get some slightly more artistic shots of the coffin; something a little more interesting and atmospheric.

I got down low and captured a profile shot of the coffin’s face:

I wanted to capture the rather beautiful Anubis’s (Anubii?) on the feet of the coffin, but also keeping the whole coffin in the shot. I chose to use selective focus here to have the feet in focus, then the rest of the coffin falling away into a pleasant blurriness.

Keeping the whole coffin in the photo gives you more context, but using the selective focus makes its clear to you what the most important part of the photo is.

And lastly, the coffin base has some beautifully painted hieroglyphs down each side. When you see her photographed from the front, all you see of the coffin base is the undecorated inner surface. You wouldn’t even know these hieroglyphs are there. So I captured this:

This photo needed me to crack open my wide-angle lens. Not something I usually like to do, as wide-angle lenses can easily create distortion in photos if the lens is at an angle to its subject. However, with the tiny amount of space I had, it was the best option, so I was careful to ensure the camera was straight on with the coffin to eliminate any distortion.

These last three photos are my favourites of Tasheriankh and her coffin.

The details and the full-length photos are great, and are really useful, for sure. But, give me an opportunity to do things a little differently and creatively, I can show you an artefact in new and interesting ways. I can make the object more meaningful to me and to you, and allow it to really show off its beauty and its craftsmanship. It makes me a very happy bunny.

Processing the photos in Photoshop

The photography is, of course, only half the story of these images; once I get the photos home, I get to work doing the processing on the computer.

There wasn’t much work to do with the focus-stacking – just a little bit. And the closeup details didn’t need much work beyond some work on things like contrast and tones.

The major focus of many of these photos was background removal.

Removing the backgrounds from the photos

When I photograph small artefacts, I use a sheet of black cloth or lightpad to hide whatever’s behind it. I’ll still then replace it in Photoshop with plain black or white to keep my photos consistent and clean-looking, but having a simple background of a similar colour makes removal straightforward work.

But for larger objects with a wider angle of view, it’s harder to cover everything around them to hide the surroundings. I couldn’t avoid getting parts of the organics store in these photos. This is where the background removal really comes into its own.

Take the photo of the coffin and mummy after the mask had been reattached, for instance.

The coffin was lying on white conservation paper, and you can see the floor, the wires from my lights and part of the mezzanine structure.

And, because of the metal column from the mezzanine, I couldn’t quite get the coffin central.

Cutting out the white conservation sheet and changing to a black background is harder than removing an already-dark background. With a dark background, you can afford to leave a few pixels of original background around the artefact to get a clean, precise outline.

When your background is very different in colour, you’ll get a weird, ugly halo around your artefact if you leave any of the original background in, so I had get down to individual pixels to get rid of the white, but none of the coffin.

After some straightening, processing, and the background removal, you end up with this:

And another example is the hieroglyphs down the side of the coffin. There was no way to avoid capturing half the organics store in with the coffin, unless I’d bought many metres of black fabric and hung it from the mezzanine and the front of the trolley, which would have made it hard for me to move myself, my equipment and the coffin around safely.

So again, I had to just photograph in situ:

Then do more detailed background removal in Photoshop.

This, again, was tricky in places – some of the wooden cases behind the coffin are very similar in colour to parts of Tasheriankh. I had to be careful to not accidently include bits of the background or take out any of Tasheriankh.

And finally, I also decided to do a bit of extra work on this photo of Tasheriankh without her mask on.

Although Tasheriankh’s wrappings are largely intact, her face is partially exposed, and has sustained some damage down one side.

I wanted her to keep her dignity – and to keep the focus of the photo on her beautiful chest cover – so I reduced the exposure around the damage. You can’t really see the damage in the photo, but you can in the original. I haven’t changed the photo or deleted any part of it; I just reduced the exposure around the damage to hide it.

What was it like photographing a mummy?

This was the first time I’d ever been in close contact with a mummy with no glass case or coffin lid between us.

Whilst the mummy has become an icon of horror movies and halloween fun, we have to remember that real-life mummies were once living people, just like you and me.

I worked right up close to Tasheriankh, sometimes my face mere inches from hers as I moved her into place; nothing between us except the air that I breathed.

I was by myself in a cold, dark room, lit only by my two small LED panel lights. I have to admit that the room did feel a little creepy for the first few minutes.

But, what quickly took over was that being so close to her was awe-inspiring. Just like my encounter with the Lindow Man at an exhibition when I was 13 (also at Manchester Museum), I felt connected. Connected to her and her time, even though our lives had been separated by more than 2,000 years. I found myself wondering what she’d looked like, how her life was and what she’d think of her life now in the 21st century, bringing her culture and beliefs to us. I’d hope, at least, she’d be pleased to know that her body has continued to survive for her ba – her personality – to return to each night, and that her soul lives on as we continue to speak her name: Tasheriankh.

Oh yes, and if you’re wondering, she does smell. But not in a bad way. She has a slightly sweet, musty smell, from the oils and perfumes that were used when she was embalmed. To think that I was actually smelling ancient Egypt itself was … well, to be honest … a little mind-blowing …

Rest in peace, Tasheriankh; may your soul live on for millions of years.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

A really inspiring, captivating account of a shoot! It’s great to hear your thought process and the balance of technical and artistic considerations, and I was touched and impressed by you leaving the damaged part of her face underexposed.

Aw, thanks Ben! I’m so glad you found it interesting and helpful 🙂

I think that although mummies are important archaeologically speaking, they’re people that once lived, and so should still be treated with respect and dignity.

[…] photographed several coffins and mummy covers – including the coffin of the lady Tasheriankh – for the Golden Mummies of Egypt exhibition, and while they weren’t scary to photograph […]

She’s so beautiful. I have always loved anything that’s is”Ancient “ after learning so much, but not enough, but then can anyone learn all in their lifetime. Thankyou for your posts.

Hi Kristine,

She really is lovely, isn’t she. You’re right – learning should be life-long; we’re never too old!

Thank you for your kind words; I’m very happy you’re enjoying my writing and photography!

Julia