5 reasons you might be struggling with low-light photography

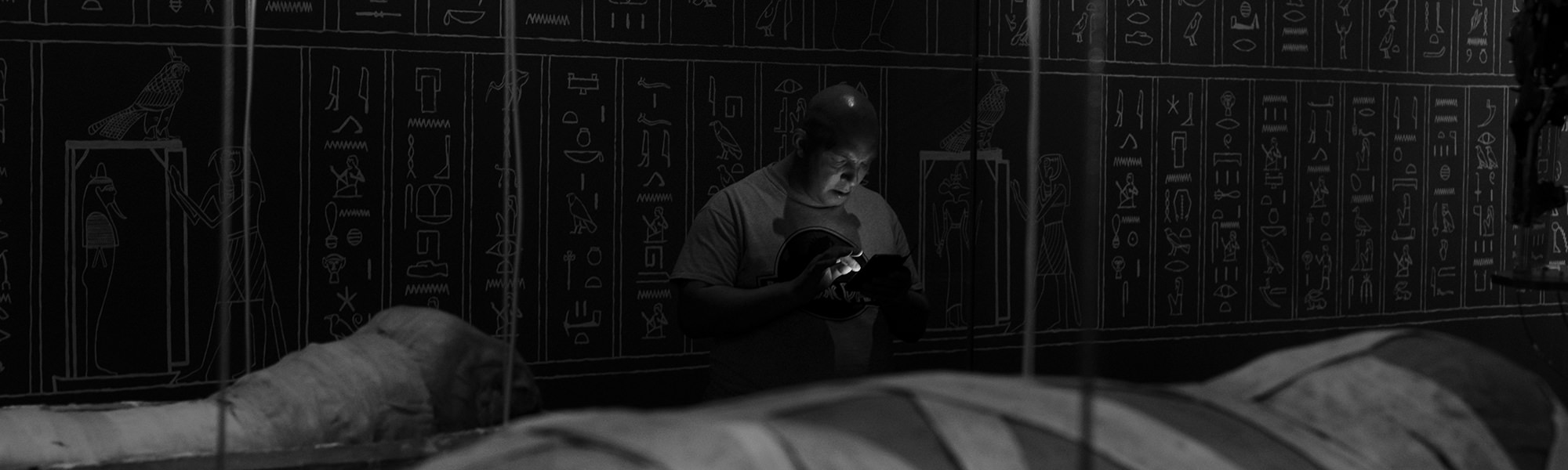

So, you’ve come home from a day at the museum and crack open those photos you snapped to share with your friends online.

But … horror! … your first photo is blurry, the next one is too dark, the one after that is all grainy, and so it goes on.

You feel a bit disappointed that you didn’t quite get what you wanted, and just find the least blurry ones from the day to share.

Believe me, I’ve done this plenty of times! Museums and galleries can be tough places to get good photographs; low ambient lighting combined with bright spotlights create high-contrast conditions that can be hard to deal with.

Sometimes, this is down to your hardware; other times, it’s just not quite knowing what to do with your camera.

If you want to bring better photos back from the museum, the first step is to start understanding why your photos aren’t working so well in the first place.

So, I’ve put together a few common reasons why you might not be getting the photos you want. Have a read and see if you can identify what problems you have and where you could be looking to improve:

1. The sensor in your camera’s too small

Every time we go shopping for a camera or smartphone, we’re sold on the megapixel (MP) count of the camera’s sensor. A 24 MP sensor has 24 million pixels on it. Loadsa pixels! That’s got to be better than 20 MP, or 16 MP, right?

Not always, I’m afraid, because not all pixels are created equal.

Each pixel on your sensor captures light when you press the shutter button on the camera. Different cameras have different sensor sizes and so the physical size of the pixels themselves can vary.

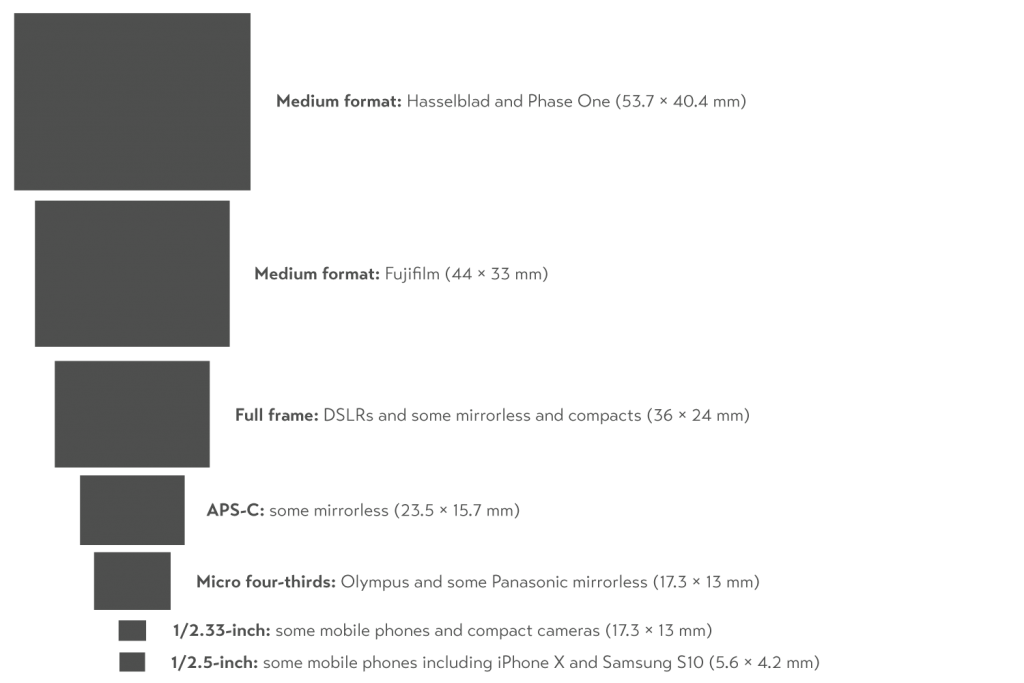

The graphic below has a few of the more common sensor sizes. Small sensors, such as those found in mobile phones and some cameras, are tiny in comparison to medium format, full-frame and APS-C sensors.

This should help you understand why megapixels alone don’t tell you how good your camera is. If you had a full-frame camera and a mobile phone both with a 24MP sensor, just going on pixel count alone, you’d think they should fare quite equally in low light. However, when you compare the sizes of the two sensors, it becomes obvious that in order to fit 24-million pixels on a phone’s sensor, you’d have to make the actual pixels smaller than those on the full-frame sensor to fit them all in. Smaller pixels can’t capture as much light as larger ones.

Smaller sensors with smaller pixels aren’t usually a problem in good light. But when light’s at a premium, you need bigger pixels to capture what light’s available. It sounds weird to say it, but if you have a smaller sensor, you’re probably better off with a lower pixel count, as the pixels themselves will be bigger.

If you’re not sure what sensor size you have in your camera, just Google your camera’s make and model + sensor size, and you should be able to find it.

2. You’re taking photos as JPG instead of RAW

We all know about JPGs; they’re picture files. We share them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and it’s how our photos come out of our mobile phones.

Many cameras, however, can take photos in the RAW file format as well as JPG. RAW is an image file format, just like JPG, but has a significant difference.

JPG is a compressed file format, also known as a ‘lossy’ format. The camera compresses the data it’s captured to make a smaller, more usable file. But, this means some of the original information collected by the sensor is lost.

RAW files are the opposite. They contain literally all the raw data your camera has captured, so there’s more information in the file to work with. This is great for low light; if your photo has a lot of shadows or dark areas, you can often brighten them up a little and find details you’d otherwise have lost.

The downside to RAW files is that they’re bigger (because they contain more data), and the photos have to be processed and saved out as JPGs, TIFFs or PNGs before printing or sharing online.

Some cameras, unfortunately, don’t have the ability to shoot in RAW. But, many do, and an increasing number of mobile phones do as well. Have a look and see if you can. It’ll be in your camera’s menu settings under something like ‘image size’ or ‘image quality’, or under ‘pro’ settings on your phone. If you like having JPGs to hand, set it to shoot in both RAW and JPG, then at least you have the RAW there as a backup.

3. Your shutter speed’s too slow

When you use your camera on automatic mode, or on aperture priority or shutter priority, you’re allowing the camera to make decisions for you. This can be just fine when the light’s good, but when the light’s low, your camera doesn’t always make the right decision for you.

Your shutter speed is, simply put, how long your sensor is exposed for when taking a photo. This is usually measured in seconds or fractions of a second. Longer shutter speeds allow more light to be collected in your pixels. Therefore, longer shutters speeds are better in low light.

If you’re on automatic mode or aperture priority, the camera’s going to choose your shutter speed, and will choose one appropriate for getting your photo properly exposed. What your camera’s not going to take into account, however, is whether you’re holding your camera or you have it on a tripod.

When you’re using a tripod, you can go as slow as you like. Some astrophotographers, for example, will use shutter speeds of an hour or more to create those lovely star-trail photos you see online. But, when you’re holding your camera, even the steadiest of hands can only go so slow before blurriness from moving becomes a problem.

And this is why so many people come home from museum visits with slightly blurry photos.

Your camera’s given you a nice, slow shutter speed to get rid of all that low ambient lighting, and you go and ruin it all by not being a robot and moving slightly as you take the photo.

4. Your aperture isn’t wide enough

Every lens has an aperture. Inside the lens is a set of circular blades with an opening (the aperture), which are there to help the camera with focussing. You can adjust the aperture, to make it bigger or smaller, much like the iris in your eyes. You might know it as the ‘f-stop’.

To state the obvious, the wider the aperture, the more light you’ll let onto your sensor (in the same way that your pupils dilate in the dark to let more light into your eyes). So it makes sense to open your aperture right up in low light.

However, different lenses have different maximum apertures. Lenses classed as ‘fast’, i.e. with very wide maximum apertures, will go as low as f/2.8 or less. I have lenses with a maximum aperture of f/1.4 which are fantastic for low light. Many kit lenses and other zoom lenses don’t go wider than around f/3.5, which means you’ll have to slow down your shutter speed and/or crank up the ISO to get a well-exposed photo in low light.

The trade-off with a wide aperture, however, is that you’ll have a narrow depth-of-field. Simply put, this means that not so much of your photo will be in focus; think of those portraits you see where the person’s face is in focus, but the background is pleasantly blurry.

5. Your camera’s a few years old and doesn’t handle ISO well

ISO is a measure of the sensitivity of your sensor, and is found in digital cameras only (it’s a little like the ASA of film in analogue cameras). When you increase the ISO in your camera, it doesn’t change the amount of light hitting your sensor; rather, it amplifies what’s already there (like plugging a guitar into an amp). This, unfortunately, amplifies everything, including what’s known as ‘random fluctuations’ in the photo – which you might know as noise or grain. Therefore, higher ISO = more noise.

ISO capability is something that digital camera manufacturers having put a lot of work into in the last few years. Cameras released since around 2014-ish deal with higher ISO much better than older ones. Older cameras can start showing noise (as tiny little flecks of random colours) at ISOs as low as 400 or 800. Newer cameras you can push up to 6400 or higher before you start getting the same problems.

How can you improve your low-light photography?

It depends, really, on what problems you’re experiencing. Some of the issues, such as small sensors, an inability to shoot in RAW and owning an older camera can really only be cured by an equipment upgrade. If your lens doesn’t have a wide-enough aperture, consider adding to your lens collection. Look at fixed lenses (lenses that don’t zoom); they often have much wider maximum apertures than zoom lenses. Buying better lenses can often offset the need to upgrade the actual camera, and can be a much cheaper option.

If you can’t afford new equipment, start learning how to use your camera on manual mode to have more control over the photos you take. Your pictures may not be perfect, but you decide which settings will be best, not the camera. You get to decide that those dark, shadowy corners of the gallery can stay in shadow. Even if your camera’s not what you want it to be, by taking control, you will find you start taking better photos.

If you’re struggling with something like shutter speed, learning to take your camera off automatic mode and having more control over the settings can get you out of a fix.

At the very least, try using your camera on shutter priority mode, and experiment with different shutter speeds to see how slow you can go before hand-shake becomes a problem. That way, when you’re next in low light, you can make sure you don’t go slower than this minimum speed.

If you’ve never used RAW before, give it a try. You’ll need a few basic processing skills and software that can deal with RAW. However, you don’t need to be a Photoshop maestro to get your photos looking great. Have a look around on Google for software, if you don’t already have software such as Affinity Photo, Lightroom, Photoshop or Capture One. Many camera manufacturers have their own free software for processing RAW files. It may not be feature-rich, but it’ll get you started (once you start getting the hang of processing photos, it can be really fun!).

The thing to remember with low-light is that when you can’t get extra help from a tripod or external lighting, there’s often a trade-off. You may need have your ISO a little higher and have a bit of grain in your photo. You may need a wider aperture and have less of the photo in focus. But, selective focus and a bit of grain, in my opinion, is better than shaky, blurry photos. Much better.

What do you struggle with when taking photos in low light? Me, it’s often shutter speed; with my dyspraxia and hypermobility, I don’t have a particularly steady hand, so I have to increase my ISO and have wide apertures to compensate. Share your problems or ask my advice in the comments below.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!