Photographing flint tools using a lightbox

It can be all too easy to think that doing artefact photography is routine, a bit samey and perhaps … dare I say it … a tiny bit dull.

Nuh-uh! Not so. Especially if you’re able to be a bit investigative and curious.

Doing the photography for the Before Egypt exhibition, I needed to photograph some flint tools and stone palettes.

In particular, there were two pieces on display in the Garstang’s Predynastic case that we needed to get in front of my macro lens. One is a fish-tail knife; the other, a tiny, agate arrowhead. Because these pieces are translucent, I decided to try photographing them over a lightbox to see how shining a light through them could capture detail and bring out their beauty.

So, with these two flint tools, plus a small palette and a fragment of a quartz bowl, I headed down to the imaging suite.

Using a lightbox to photograph the objects

I used the lightbox in the departmental imaging suite. It’s quite a simple set up: a wooden frame topped with a glass plate, and a lightpad underneath. The artefact sits on top of the glass with the light shining from underneath it, and my camera above, looking down. I was really quite excited to get going with the photography to see what I could come up with.

I did some focus-stacking on all the objects, despite their not-very-thickness. This is the case with a lot of macro photography, because the closer your lens is to an object, the narrower your depth-of-field (how much of the object’s in focus). So, even an object that’s only a few millimetres thick can benefit from focus stacking.

Agate arrowhead (1.6 cm)

I photographed both sides of the arrowhead, using just the lightbox underneath to light it. I then added in a second light to create some raking side light to try to bring out the uneven surface.

It’s come out beautifully. Really beautifully.

Apart from the focus-stacking, these images have needed barely any processing at all. A little bit of cropping to get the arrowhead centered, plus a tiny bit of contrast tweaking, and I’ve replaced the background with a plain white one (the glass plate had a few marks that I just couldn’t clean off). That’s all.

The image on the left has just the light coming through from underneath; the image on the right also has the sidelight.

I love them both, but I like the one without the sidelight a little more. There’s just a bit more detail and depth to see, and I prefer the wider range of tones.

(The small, dark blotches you can see towards the right-hand-side is the accession number written on the underside.)

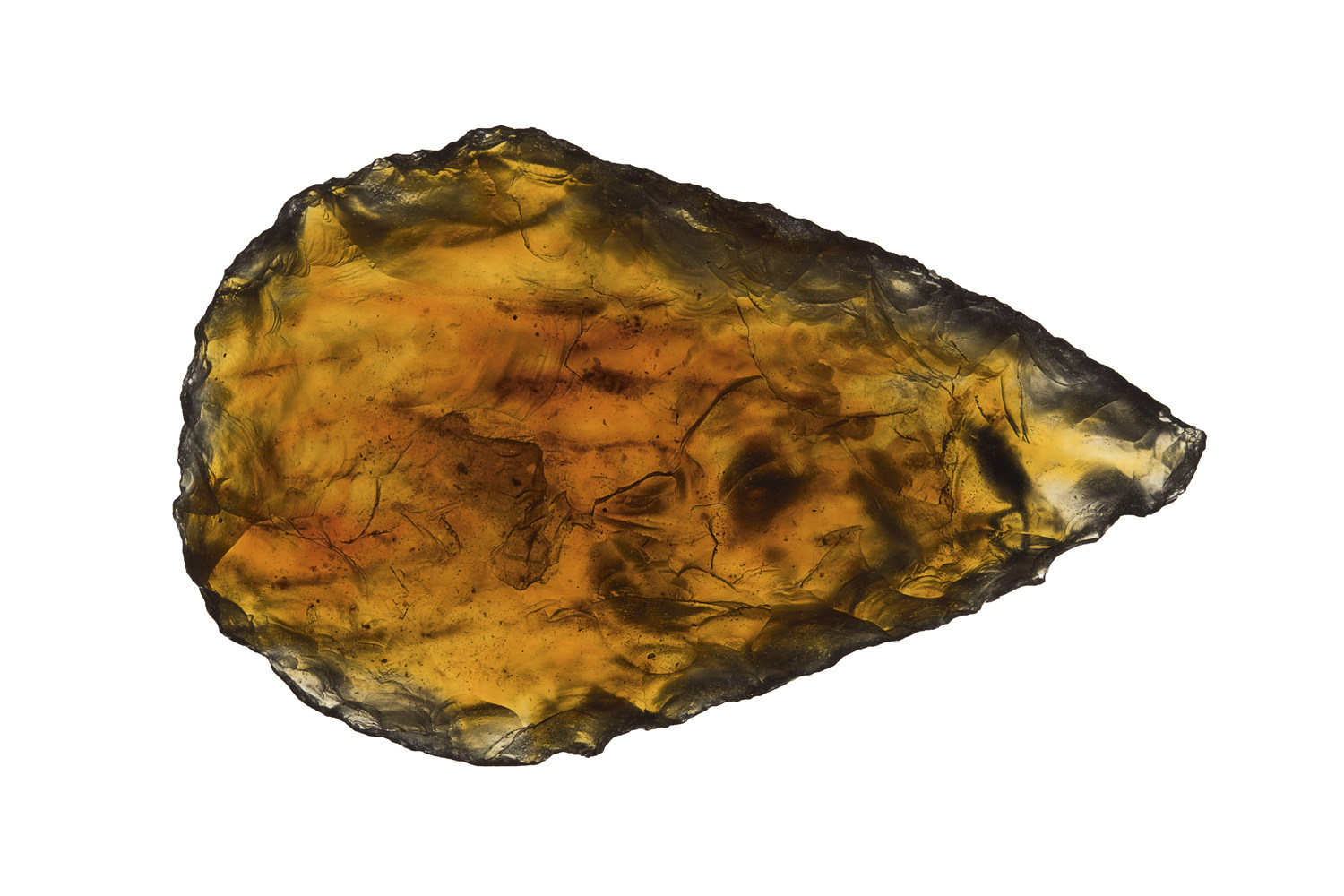

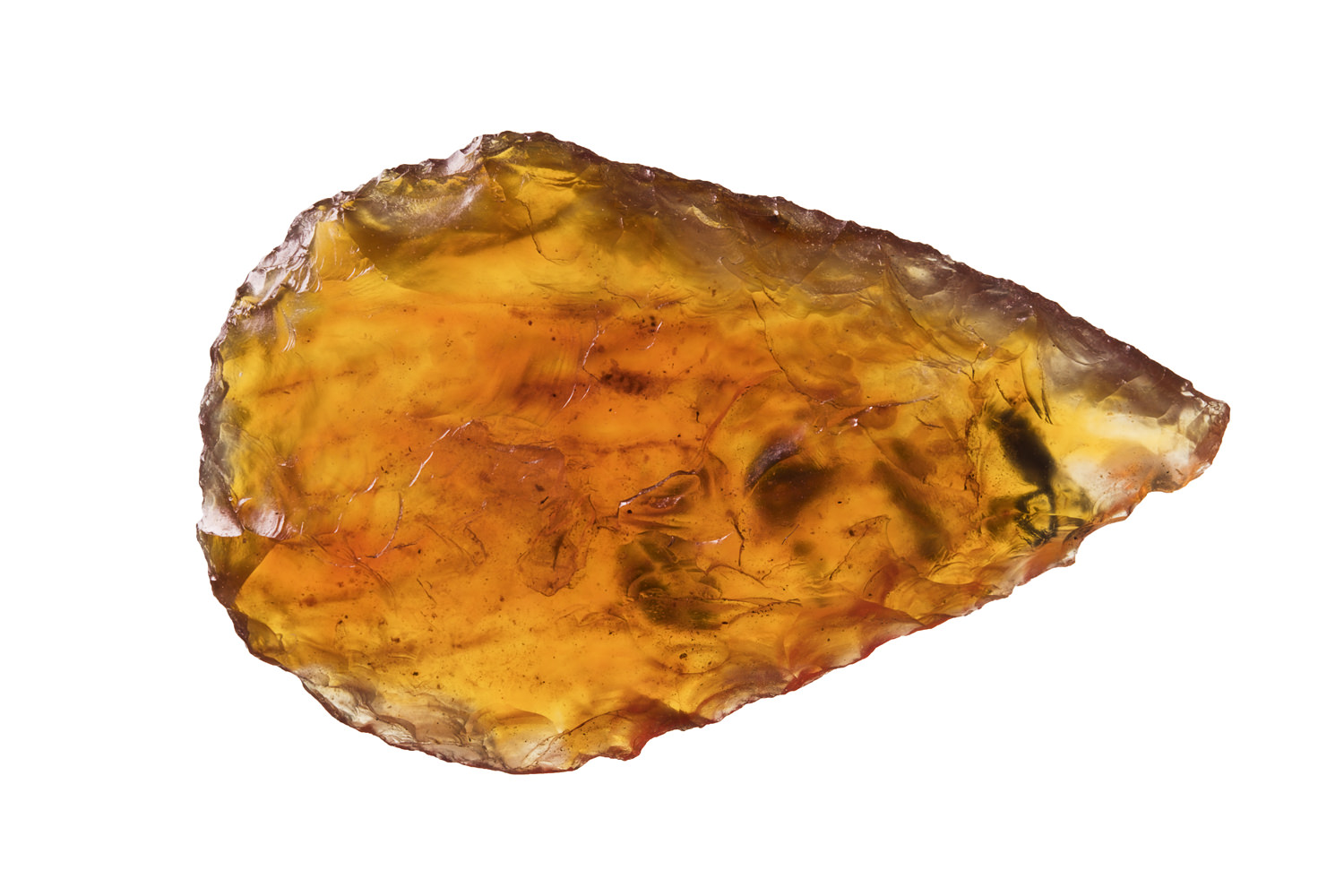

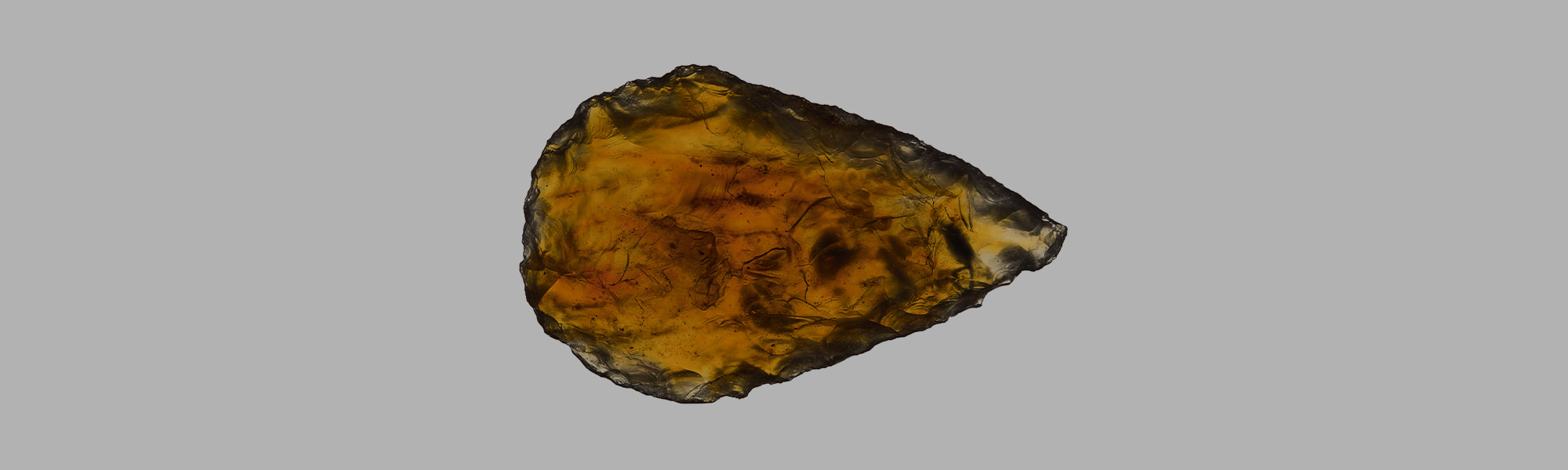

Fish-tail knife (12.5 cm)

The fish-tail knife I also photographed using first just the lightbox, and then second with both lightbox and sidelight. I also then did a bracketed exposure to create an HDR image (explained below).

It’s a beautifully crafted object. In the photos below, you’re seeing it side on. The handle is on the right, with the dual blades on the left. The serrated edges are just amazing; so meticulously crafted. Remember: the blades on this knife are around 6 cm in length.

What is HDR photography?

HDR stands for ‘High Dynamic Range’, and is a technique most often used in landscape and architectural photography.

It allows you get more detail in your photo than your camera would usually allow. The human eye can see a far greater range of tones than cameras can (tones relate to the range of brightness, from light to dark). When we’re somewhere with a mixture of shade and bright light (such as temple ruins or dappled woodland), our eyes can see detail in both the shadows and in the bright sky. Cameras can’t do this all at once. You end up with shadows that are completely black, or a sky that’s burnt-out white.

HDR allows photographers to recover these details that would otherwise be lost in a photo.

To do HDR photography, you take three photos instead of one, each with slightly different exposures. As well as your main photo, you also take one that’s a bit darker (to capture the details in the bright areas of the photo) and the other a bit lighter (to capture the detail in the darker parts of the photos). Many cameras have what’s called a bracketing setting that does these triple shots for you in rapid succession.

You then load the three photos into photo-editing software with an HDR function, and it does ‘tone mapping’ to create a composite image; i.e. it combines the three photos to get detail from the highlights, the shadows and the mid-tones.

You can play around with the settings in your software to adjust the amount of detail, contrast, etc. You can go with anything from a very subtle, natural look, through to something quite abstract and harsh. I try to stay within the bounds of a ‘natural’ look; if you push detail and contrast too far, you end up with what is, quite frankly, a horrible, over-sharpened image that looks almost cartoon-like. If you compare the second and third images above, the HDR one looks not much different to the second one. It’s just a little more even-looking and has a little more detail.

Personally, I’m not really a fan of (obvious) HDR photography. I like having shadows in photos; it adds atmosphere. I find photos that have every single part in high detail (especially landscapes, cityscapes etc) overwhelming to look at.

However, as with many of these things, when done well, you shouldn’t even realise it’s been used.

It has its place, and it’s also a matter of personal taste. I wouldn’t usually choose it myself, but in this particular instance, I think it’s produced the best photo.

Double bird-headed palette (6.3 cm)

This small, double-bird-headed palette is only 6.3 cm tall. Nowhere near the grandure of the large, ceremonial palettes such as the Narmer palette and the Hunters’ palette.

However, as they say, beautiful things come in small packages.

I wouldn’t ordinarily photograph a solid stone object on a lightbox (let’s face it; palettes aren’t known for their translucence), but my camera was set up already, so rather than have to take the box down and set up my tripod, it was simplest to stay as I was. And using some backlight got me a really lovely, crisp outline.

With the addition of the sidelight, it’s produced a surprisingly detailed image. All those scuffs and scratch marks on the surface come from its crafting. Seeing that really highlights the human connection; that somebody, all those thousands of years ago, sat down and poured hours into carving and levelling those edges and surfaces.

Wonderful!

Quartz bowl fragment (12 cm)

Finally, I photographed the quartz bowl fragment. I’d grabbed it from the display case as a bit of an afterthought. As the quartz is semi-translucent, I thought I’d see how it looked sitting atop the lightbox.

Unfortunately, the bowl was too thick for the light to make much of a difference. And the fragment is a little uninspiring, aesthetically speaking.

However, as I was turning the fragment over in my hands, something caught my eye just on the edge of one of the broken surfaces. Yes! It was part of a serekh … boom!

Sadly, the top half is lost, so it’s hard to tell which name is here. It’s possibly the bottom of the mr glyph in the name Narmer – one of the first kings of Egypt. But, I can’t be sure.

The serekh’s about a centimetre tall, so it’s hard to garner much detail. However, it’s always exciting to find something like this previously unnoticed on an object. And afterwards, the piece went back into the display cabinet facing the opposite way it’d come out, to show off this super little detail we’d found.

I have to say that I’m utterly made up with the results of this session. I never thought I’d hear myself say this, but the arrowhead really is up there amongst the most beautiful artefacts I’ve ever photographed. The fish-tail knife is gorgeous, as well, and the lighting I used for the palette has brought out the surface detail surprisingly well.

And it’s proof that a little creative thinking and experimentation can provide some exciting and really beautiful results.

It pays to really look at the artefacts you’re photographing. Don’t just put them in front of the camera and press the button like a factory production line. Take a moment, look closely, turn it over in your hands (or walk around it, if it’s big!), think about it for just a moment, and be brave and experiment.

You never know what you’ll come up with …

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

[…] a laptop and choose and change lenses is really handy. I find myself photographing everything from 1.6 cm-long arrowheads with a macro lens to 2 m-long coffins with a wide-angle lens, as well as documenting people setting […]

[…] a laptop and choose and change lenses is really handy. I find myself photographing everything from 1.6 cm-long arrowheads with a macro lens to 2 m-long coffins with a wide-angle lens, as well as documenting people setting […]

[…] stone and flint tools […]