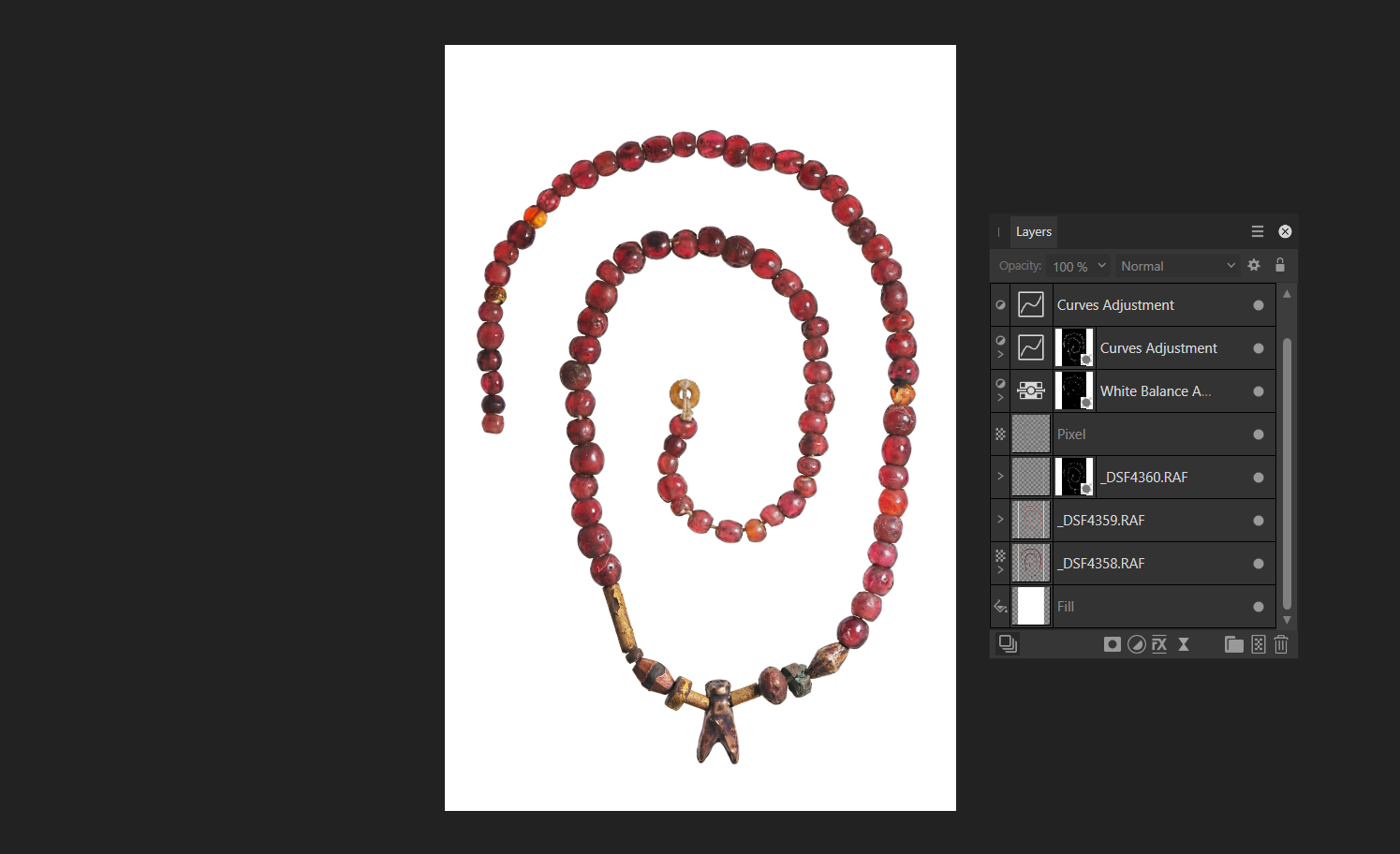

Artefacts in focus #2: a string of carnelian beads with a fly pendant

Back in mid-2023, before The Great ME/CFS Crash of 2023, I photographed a number of artefacts at the Garstang Museum of Archaeology to be used in their online exhibition accompanying the Creatures of the Nile exhibition hosted by the Victoria Gallery and Museum.

One of those objects was a string of beads with a pendant of a fly which is, in my opinion, a fascinating piece both historically and photographically. So it’s my choice piece for this second Artefacts in Focus article.

About the necklace

The necklace (I don’t know that this was originally a necklace, but for want of a better word, that’s what I’ll use here) comprises 80 carnelian beads, 10 other assorted beads and a small fly pendant. The carnelian beads are small and round, the largest ones perhaps just half a centimetre big.

The fly pendant is plain, without much detail except for a little shaping around the head with a single hole for stringing at the neck.

It’s described in the museum catalogue as being made of copper alloy, and has some interesting patches of pink colour in it. I don’t know what these are, whether it’s something you’d expect to find on something made of copper alloy, or if they indicate it’s actually made of something else (such as electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, often found with other inclusions of other metals such as copper). Any readers here who know their metals and alloys, I’d love to hear from you!

The whole necklace measures 27.1 cm, and the fly pendant comes in at 1.1 × 0.6 cm.

Unfortunately, there’s not much I can tell you about where and when this amulet came from. It’s unprovenanced meaning it was bought from an antiquities dealer or market, donated to the museum by a private collector, or excavated with no record made. Or possibly a combination of all three. (This is a common problem with early excavations, where recording of finds was patchy or non-existent, and the colonial attitudes of ‘treasure hunting’ meant artefacts were just bought or taken with little regard for recording their historical context.)

This means that we can’t even know if the beads and pendant were originally part of the same piece, or if they were cobbled together from different finds (the stringing is a modern(ish) addition).

There are some things, however, we can surmise.

Firstly, I would suspect that the way the beads have been strung isn’t an accurate reconstruction, because the ancient Egyptians regarded symmetry, harmony and balance as an essential aspect of their design. Considering the central portion of beads around the fly pendant aren’t symmetrical, I doubt they’re in their original layout.

Secondly, despite the lack of provenance, we can at least suggest an estimated date.

Although amulets of flies have appeared throughout ancient Egyptian history – the earliest examples dating to the Predynastic Period (c.5000–3000 BCE) – these metal examples first appeared in the First Intermediate Period (c.2181–2055 BCE), with the majority dating to the Second Intermediate Period (c.1782–1550 BCE) and New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BCE). So we’re possibly looking at a date – for the fly pendant, at least – of between 1782 BCE and 1069 BCE, perhaps a little earlier or perhaps a little later.

But all this talk of fly pendants and amulets begs an interesting question:

Why a fly?

Unlike many other animals, where we can be pretty sure of why the ancient Egyptians venerated them, or what it was about them the Egyptians hoped to emulate, their relationship with flies is obscure.

From a modern perspective, we may be prone to thinking, ‘Ew, flies!’ because they’re annoying, near impossible to catch, and are known to spread illness and disease. But the fact that ancient Egyptians wore amulets of these creatures around their necks would suggest their attitudes were a little different.

The accepted theory, since 1911 when it was proposed by Kurt Sethe, was that it was the persistence and evasiveness of flies that led to versions made of gold or electrum being awarded as medals of valour.

The most famous example of gold fly ‘medals’ are those found in the tomb of Queen Ahhotep, the mother of Ahmose I – the king who brought the years-long war to expel the invading Hyksos to a conclusion – leading to her being referred to as a ‘warrior queen’.

And so this is how you’ll usually find fly pendants described. For example, in The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt1:

… the iconographic significance of flies is best known during the New Kingdom, when the military decoration known as the ‘order of the golden fly’ (or ‘fly of valour’) was introduced, perhaps because of flies’ apparent qualities of persistence in the face of opposition.

Interestingly, however, Taneash Sidpura’s PhD thesis, Flies, Lions and Oyster Shells: Investigating Military Rewards in Ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period to the New Kingdom (4000-1069 BCE), disputes the assumptions that golden flies were awarded as medals of honour.

To try to cut a very long story short, Sidpura argues that:

- the flies in Queen Ahhotep’s tomb being military is a circular argument. The flies must be related to military activity because Ahhotep was a ‘warrior queen’. Ahhotep was a warrior queen because she had golden flies in her tomb. You see the problem there;

- the majority of golden flies for which we have context (knowing where they were found) belonged to women, not men;

- the only two texts upon which Sethe’s theory was built come from tomb inscriptions of Ahmose Pennekhbet and Amenemhab Mahu, both military men. They refer to jewellery, weapons, gold flies and gold lions being bestowed upon them by the king, and Sethe made the assumption – with no supporting explanation (Sidpura, pp. 24–25) – that these gold flies must be awarded as part of the ‘Gold of Valour’ (nebu en khenet), as a military award rather than just part of a generic award of valuable things from the king.

To take a deep dive into all this is well beyond the scope of this article, but if you wish to read more about Sidpura’s research, you can find his full thesis via the link above, or for a more concise version, he’s written a piece for The Past website.

So where does that leave us with the symbolism of this fly pendant? Not really any better off, to be honest (sorry!). It’s possible that fly pendants were intended to help protect the wearer against the disease that real flies can spread, as well as symbolising rebirth: flies lay their eggs in decaying matter, so the analogy of life springing forth from death is clear.

About the photography

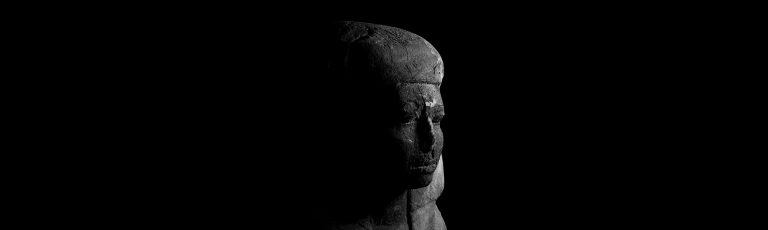

I made two images of this piece: the one at the top of this article, of the whole necklace, and then a detailed shot of the fly pendant (below).

I laid the necklace out in a spiral shape, mainly because that’s one of the most efficient layouts to be able to get as close to the beads as possible. Laying the necklace out straight, or in a circle would have meant I’d have had to have the camera further away.

I used my lightpad (a tablet-shaped LED light that lies flat on the table, usually used for viewing photographic negatives or by artists for tracing) as the carnelian beads are slightly translucent, so shining light through the beads highlights the natural patterns in them and the string running through them, as well as making them ‘pop’ visually.

The necklace

I didn’t need to focus stack the necklace, though I did use exposure bracketing – taking photos at three different exposures – to get the best out of the beads, so this image is a composite made from three photos.

You might have noticed the extra string in the original images:

When I photograph strung objects like this, I remove excess string during editing. The string is modern, it’s not part of the original artefact, and it’s just a bit distracting. I don’t remove all the string, such as the knot around the bead at the other end of the necklace, otherwise I’d have to remove part of the bead itself, or use the software tof ‘clone’ or use a generated fill to digitally recreate the bead. This isn’t something I’m willing to do, because I’d be asking AI to decide what it thinks should be there, then you’d no longer be looking at the actual artefact.

So it’s an exercise in moderation: remove that which can be easily removed, or which doesn’t impinge upon the artefact to improve the end image, and then just leave the rest.

The background removal itself took a while, going around the edges of all the beads, but once it was done, the rest was relatively straightforward. I painted through parts from the other two exposures, added a little sharpening and worked on the contrast a little.

The fly pendant

Photographing the fly pendant was a different matter.

I kept it on the lightpad because although it’s not translucent, I get a nice, crisp outline, which is really important when working that close up.

The pendant is only 1.1 cm long, so it’s here that the macro lens becomes irreplaceable.

Of course, getting up really close means that my depth of field becomes really, really narrow, so focus stacking is unavoidable. To get the whole pendant in focus took 50 photos, and so when you take into account the three exposures again, it’s a total of 150 photos to make the final image.

The focus stacking produced three TIFF files, which, again, I layered up in Affinity Photo, removed the background, then worked on the exposures and the contrast and shadows. The finished product is a detailed, sharp, high-impact and informative image of an object the naked eye would struggle to make much of.

- Shaw and Nicholson, The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London, 1995), 101. ↩︎

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

[…] photo of the beads is on the Sky page of the online exhibition, and I’ve written an article giving more about the object and how I went about photographing it […]