The goddess Isis: mother, magician, healer, wife

The goddess Isis, along with Osiris, is undoubtedly one of the best known deities from ancient Egypt. The couple are synonymous with the seemingly mysterious, often-confusing religion. First attested in funerary texts from the pyramid of Unas (c. 2360 BC), Isis was the longest lived of the Egyptian pantheon. Her cult became dominant in the Greco-Roman period, with the goddess soaking up aspects of other goddesses including Hathor and Astarte until she became the ultimate, all-powerful deity. The last, and arguably most famous pharaoh, Cleopatra VII, often depicted herself as Isis.

Because her cult was adopted in Rome, it spread far outside of Egypt, sanctuaries being founded even as far north as London. Her temple at Philae was the last temple to close in Egypt in the 6th century AD after Christianity spread across the Roman Empire.

Who was the Goddess Isis?

Trying to ‘explain’ an Egyptian deity isn’t always an easy job. Over time, a god could develop, mutate, and sometimes adopt parts of other gods. They could transform into other gods temporarily (such as Hathor turning into Sekhmet in The Destruction of Mankind). They could even become composite deities, such as Amun-Re or Ptah-Sokar-Osiris.

However, instead of worrying about lots of details and variations across ancient texts, we can look at Isis as an overall personality.

They say that behind every great man is a great woman, and this is certainly true of Isis. Her two main starring roles were as the wife of Osiris and mother of Horus, and they certainly wouldn’t have got where they did without her.

The wife of Osiris

The Egyptian pantheon is full of triads – groups of three deities making a family unit of father, mother and child. Osiris, Isis and Horus was one of these.

(Isis and Osiris were also brother and sister. Sibling marriage wasn’t a thing in ancient Egypt except when it came to the pharaoh, who would often marry his half-sister. This would’ve been a move to protect the throne from ‘outsiders’. Now, whether pharaohs kept it in the family because of the Isis-Osiris myth, or the myth was created to justify genetically dubious partnering isn’t clear, but it’s probably the latter.)

The death of Osiris is a very famous piece of mythology. Briefly put, before the time of man, Osiris ruled over the Earth. His jealous brother Seth killed him to take the throne. Isis then used her powers of healing and magic to resurrect Osiris for long enough to conceive Horus, before the god then left this world to become ruler of the underworld.

You might be aware of stories of Seth dismembering Osiris and scattering his parts across Egypt. Or Seth tricking Osiris into getting into a coffin and nailing it shut. Unfortunately, ancient Egyptian sources are vague. These details were written down by people such as Plato much later on in time, when the myths may have developed or been exaggerated over time to make a good story.

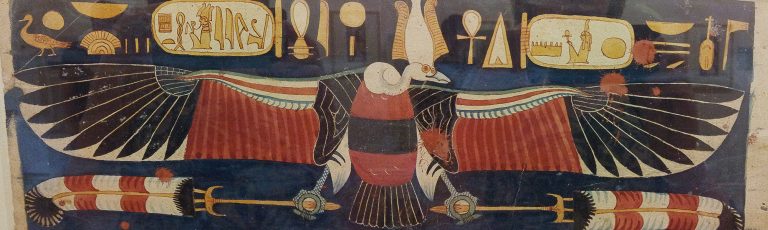

However, the iconography of Isis suggests at least some of this is true. Isis and her sister Nephthys could be depicted as kites (the birds, not the things we fly on strings). This matches up with the part of the myth where Isis and Nephthys turn into kites to search across the land for all the bits of Osiris. Kites are scavengers, who circle around looking for dead animals to eat. Their call is high-pitched and sounds mournful. Like that of a grieving widow. So, the later writings are based at least in some truth.

Because of this act of extreme mourning from the two sisters, coffins would sometimes be adorned at either end with images of the goddesses with outstretched wings, mourning the deceased and bringing breath to them in the afterlife with their beating wings.

So, without Isis – without her persistence, her magic and her love – Osiris would have remained slain, Seth would’ve remained king of Egypt, and Horus would never have existed.

The mother of Horus

After Osiris retreated to the underworld and Seth was on the throne of Egypt, Isis went into hiding. She feared that Seth would harm her unborn child to protect his place on the throne.

During Horus’ childhood, Isis was the model mother. She dedicated herself to his wellbeing. As was the way with children before the days of modern healthcare, he suffered almost continual illnesses and injuries. Isis used her powers of magic and healing to cure his every ailment.

When he was old enough, Isis brought him before the council of gods and demanded he be given his throne as rightful heir to his father, Osiris. The council were divided over whether inheritance should overrule experience, and so a most epic legal battle ensued.

And when I say epic … Isis and Horus spent eighty years – yes, eighty years – trying to win their case.

The whole saga is detailed in The Contendings of Horus and Seth, which I shan’t retell in its entirety here, because it’s a bit long (you can get the full translation in Miriam Lichtheim’s Ancient Egyptian Literature Volume II).

However, to give you an idea of the lengths that Isis went to for her son:

- when the gods retreated to an island to discuss the issue, they banned Isis outright from coming along and interfering. She magically disguised herself as an old woman and tricked the ferryman Nemty into taking her to the island (for which he later had his toes chopped off!). She then changed into a beautiful young woman and tricked Seth into judging against himself.

- when Horus and Seth transformed into hippos to fight in the water, Isis went to harpoon Seth. She accidentally harpooned Horus first (oops!), then, when she did hit her target, he threw a bit of emotional blackmail at her about being her brother. She forgave him and withdrew the harpoon. For this Horus leapt out of the water in anger, beheaded her, and disappeared off up a mountain, her head under his arm. This isn’t the end of Isis, but unfortunately the text doesn’t tell us how she was revived.

- finally, there is the highly questionable section that involves male rape (Seth on Horus), Horus catching Seth’s semen in his hands and going to Isis for help. Isis then throwing said semen into the river then helping Horus ‘catch’ some of his own semen which she then tricks Seth into eating. Seth then telling the gods of what he did to Horus (as a show of power and of Horus’ weakness); Thoth calling forth all the various bits of semen; Seth’s coming out of the water, from where Isis had thrown it; and Horus’ coming forth from Seth’s forehead as a golden solar disk, which Thoth took and wore himself. Uh-huh. As I said … questionable.

Horus does, eventually, get his throne, but it takes Osiris sending a letter from the underworld threatening to release all his scary demons if Horus isn’t crowned before it happens.

So, again, without the help of Isis, Horus probably wouldn’t have survived his childhood, and if he did, he certainly wouldn’t have made it through the battle for the crown of Egypt. I think we can all agree that, at times, Isis certainly went above and beyond the call of duty when it came to her role as mother.

How to spot an Isis

Considering the name ‘Isis’ is probably one of the most well-known Egyptian names, it’s funny to think that it’s not actually the name of the goddess.

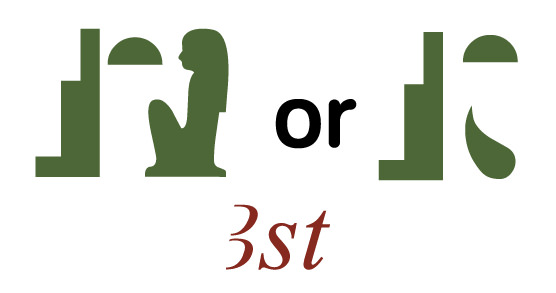

‘Isis’ is, in fact, the ancient Greek rendering of the name. Her ancient Egyptian name was Aset, written using the hieroglyph of a throne shown in profile. This hieroglyph was usually accompanied by the semi-circular bread glyph, t, and a seated woman (a determinative, which had no sound value, but helped to determine the meaning of a word). Isis was, quite literally, the throne of Egypt, on which her son Horus sat.

Occasionally, you might see the woman glyph replaced with a blobby glyph which, believe it or not, is a piece of meat. This glyph was also a determinative for the word ‘vagina’. In modern terms, this could be taken so much the wrong way. However, the glyph was probably making reference to Isis as the one who gave birth to the king of Egypt.

When you’re out and about in a museum or Egyptian temple, the easiest way to find Isis is to look for a woman with a throne on her head:

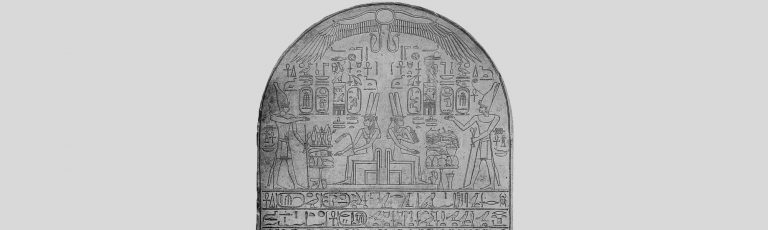

You might also see Isis with her sister Nephthys; they were a bit of a power duo when it came to mourning the dead. (As an aside, ‘Nephthys’ is also a Greek rendering. Her actual name was ‘Nebt-Hut’, ‘lady of the mansion’.)

However, unfortunately for us, in later times, Isis started to borrow (steal?) Hathor’s headdress of the sun-disk inside a set of cow’s horns. This could make the two ladies very difficult to tell apart.

In these instances, if you’re not sure, you need to look for the name of Isis.

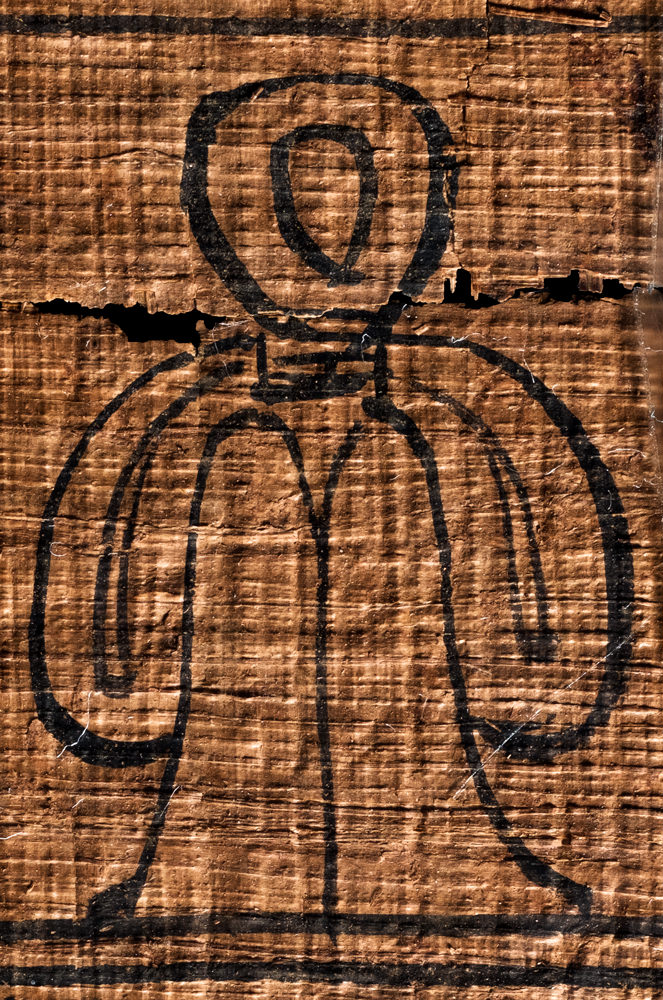

Another very common way of depicting Isis, at least from the Late Period and into the Greco-Roman times, was as a seated mother nursing the infant Horus. As I said above – Isis was the throne of Egypt upon which the king Horus sat. This imagery was so prevalent that it eventually morphed into the more famous image of the Madonna nursing the baby Jesus. (Early Christianity blossomed in Egypt; the country was even the birthplace of monastic life.)

Isis and the tyet

During the New Kingdom, the tyet-knot became the symbol of Isis. The amulet was placed within the bandages of mummies to invoke the protective powers of the goddess. The tyet was one of a small group of powerful amulets – including the djed-pillar and papyrus column – that were important enough to have their own spells in the Book of the Dead. Spell 156 reads:

You have your blood, O Isis; you have your power, O Isis; you have your magic, O Isis. The amulet is a protection for this Great One [the wearer of the amulet] which will drive away whoever would commit a crime against him.

The instructions for the spell was for it to be spoken as the amulet was placed on the neck of the deceased at interment. It also stated:

As for him for whom this is done, the power of Isis will be the protection of his body, and Horus son of Isis will rejoice over him when he sees him; no path will be hidden from him.

We don’t know for sure why the tyet became associated with Isis, but there are a couple of theories.

Firstly, in earlier times, the tyet was often depicted alongside the djed-pillar. As the djed became associated with Osiris, so the tyet became Isis.

Another idea is that the tyet was a knot of fabric used to stem the flow of menstrual blood and employed by Isis when she was pregnant with Horus to protect the unborn child from his vengeful Uncle Seth. This makes some sense considering the preference in the spell’s instructions for the amulet to be made of red carnelian, as well as the mention of blood.

But, regardless of the route taken, the tyet became the representation of Isis for those who wished to invoke the protection of the goddess. It was a symbol synonymous with protection from harm and healing.

Conclusion

All things considered, Isis was a woman who embodied the ideas of love, motherhood, devotion, forgiveness, intelligence, persistence and wellbeing. Harpooning aside, she was quite the pacifist. She didn’t charge in, all guns blazing, to get what she wanted. Instead, she used magic and cunning to win the day.

It may seem a little ‘old-fashioned’ to applaud a female deity whose most significant role was as a wife and mother, but she was of her time, when most women were bound to domesticity because of the requirements of motherhood (though women in ancient Egypt did have a better deal than those in many other ancient civilisations). But, she was also a powerful, high-achieving woman. When Osiris ruled Egypt and decided to go off for a wander around the world, rather than have his brother Seth stand in on the throne, Isis was the one who took care of Egypt in his absence. This was often reflected in reality when queens would rule in place of their husbands off on military duty, or become regent when the pharaoh died before his heir was old enough to rule.

Isis was the one who was suspicious of Seth and saw his jealousy while Osiris merrily skipped through the meadows, unaware of his impending doom. She searched the land high-and-low for her husband, mourning her one and only true love. She protected her son with vehemence and vigour. She was the mother, healer and protector of the king of Egypt.

I shall leave you now with this most amazing aria, O Isis und Osiris, from Mozart’s crazy, Masonic, Egyptianesque masterpiece, The Magic Flute:

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

[…] of the Osirian triad amulets of the Late Period (despite there not being an Osiris in sight). On the left is Isis, her sister Nephthys on the right. In the centre, holding the hands of his mother and aunt, is […]

[…] of the Osirian triad amulets of the Late Period (despite there not being an Osiris in sight). On the left is Isis, her sister Nephthys on the right. In the centre, holding the hands of his mother and aunt, is […]