‘Meroë: Africa’s Forgotten Empire’ exhibition at the Garstang Museum

Friday, 13 May 2016 was Light Night in Liverpool; a night when the city of Liverpool comes to life with family events, late-opening museums, libraries and galleries, and a whole host of arts-based fun. For the past two years, the Garstang Museum of Archaeology taken part in Light Night. Last year, they welcomed the Garstang Mummy back to the museum after a sixty-year sojourn in the Department of Anatomy. This year, Light Night was the opening night of the exhibition, Meroë: Africa’s Forgotten Empire.

Meroë and Nubia: a brief primer

Meroë was a city in Nubia, the country at the southern border of Egypt. Nubia was Egypt’s only true next-door neighbour, stretching from from Aswan, at the first cataract of the Nile, down to modern-day Khartoum. Egypt was shielded to the west by desert, to the east by desert also and the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean to the north.

Because of this, Egypt and Nubia had a unique relationship. They started to develop, culturally speaking, around the same time – 4000 BC – although Egypt then began to advance at a greater rate from around 3000 BC. This was probably due to the vaster tracts of fertile land in Egypt; much of Nubia was hard to farm and couldn’t support a population as large as Egypt’s. However, what Nubia lacked in farmland, she made up for in tradable goods. The country had gold, semi-precious stones, copper and hard stone (such as diorite). She was also beautifully placed to connect the Mediterranean to more southern regions of Africa, and was an important passageway for traded goods..

Egypt and Nubia had a bit of a rollercoaster relationship over the centuries. At times, they traded peacefully; other times, not so much. Egypt annexed parts of the country at times, and built strings of fortresses to protect the resources they needed from Nubia. Other times, particularly during times of Egyptian political weakness, such as during the Second Intermediate Period, Nubia was more powerful.

The pinnacle of the relationship, from the Nubian perspective, was during the 8th and 7th centuries BC, when Nubian kings took the throne of Egypt: the ‘Kushite’ 25th Dynasty. These kings, however, were ousted by Assyrian invasions of Egypt in the mid 7th century BC. The next couple of centuries remain a bit of a mystery as the archaeological record is bare.

The 3rd century BC saw the rise of the civilisation again, Meroë, in particular (whose existence has been attested in the archaeological record since at least 800 BC). Meroë is far down in the south of Nubia, about 200 km northeast of Khartoum. She was an industrial city, a royal residence and, crucially, positioned next to a particularly fertile area of grassland. Her strategic position, both agriculturally and industrially, allowed her to grow in power. The area remained a passageway for trade goods and, when Egypt became part of the Roman Empire, trade continued vehemently (albeit following a number of skirmishes between Rome and Nubia).

Meroë’s industry focused primarily on iron smelting, trading as far afield as India and China. However, they also traded textiles and ceramics, and continued to pass ‘exotic’ goods from further south in Africa through to the Mediterranean. Although heavily industrial, Meroë also boasted grand edifices including several temples, palaces and a lot of pyramid tombs.

Due to her importance in the trade industry and the close relationship shared with Egypt, the culture of Meroë was a real mix-up of African, Egyptian and Greco-Roman influence, Egyptian in particular. Many of their gods were Egyptian in origin, they buried their kings in pyramids (Nubia has more pyramids than Egypt) and the script that developed during the Meroitic period was a derivation of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The exhibition: a closeup

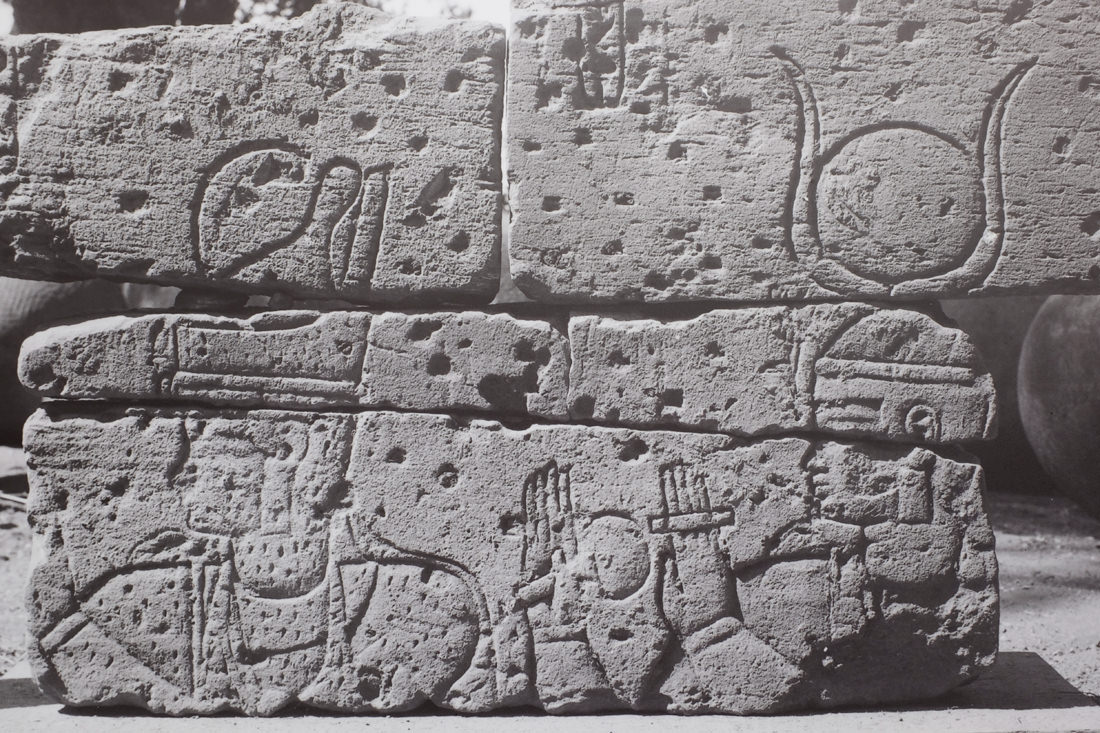

The exhibition – primarily a photographic one – is in a single room within the Garstang Museum. Around the perimeter of the room are gridded metal stands, onto which photos are mounted. The photographs are enlarged prints of pictures taken during John Garstang’s excavations at Meroë in the years 1910–1914, embellished with a collection of excavated artefacts in a display case in the centre of the room.

The artefacts show an interesting cross-section of Meroitic culture, such as their finely crafted ceramics, religious iconography and styles adopted from other cultures.

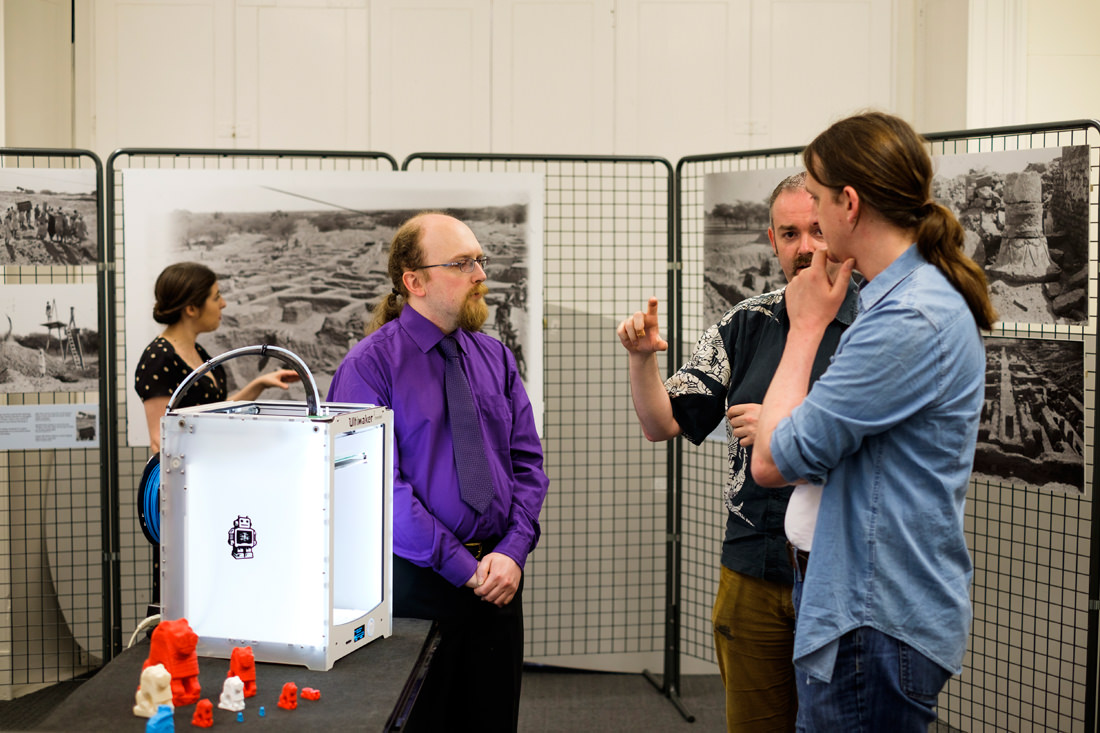

Alongside the artefacts sit a collection of 3D-printed pieces. These are genuine artefacts which were scanned and then printed out to create replicas.

Visitors are welcome … nay, expected … to pick up these replicas and have a play. And I recommend you do; you can have a really good, closeup look at ancient artefacts without risk to the original.

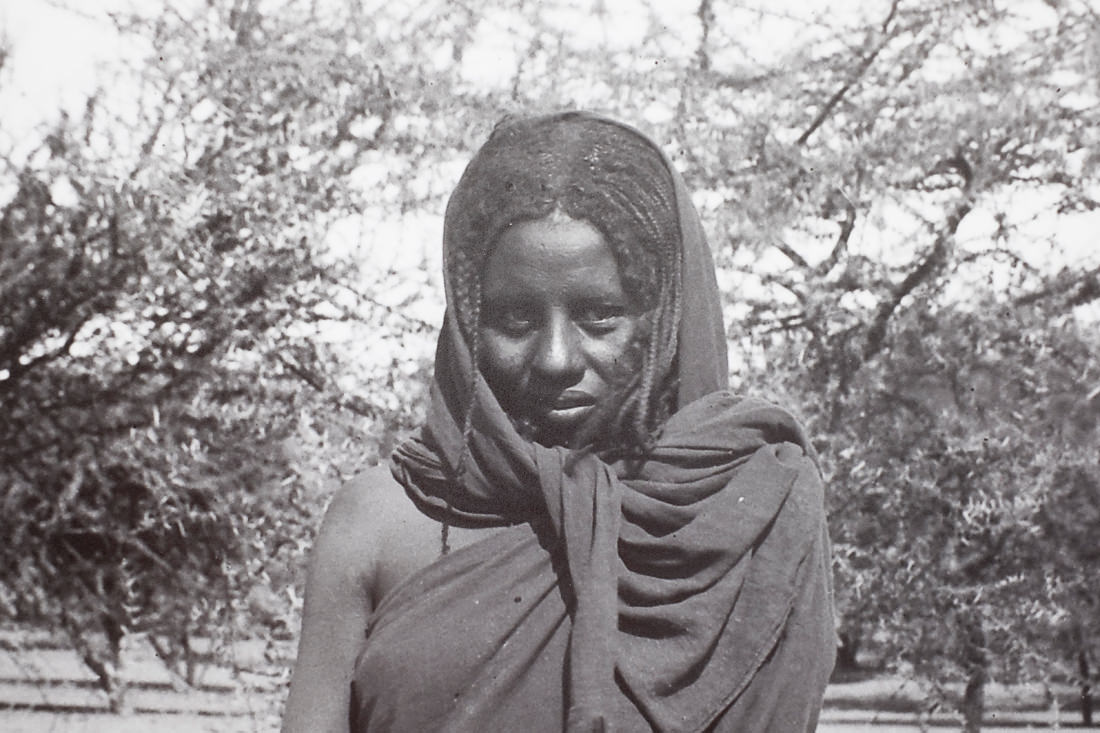

The photos themselves are a wonderful mix of archaeological photos and pictures of a more documentary nature, capturing local people and everyday sights he saw during his time in the country.

Light Night and the 3D printer

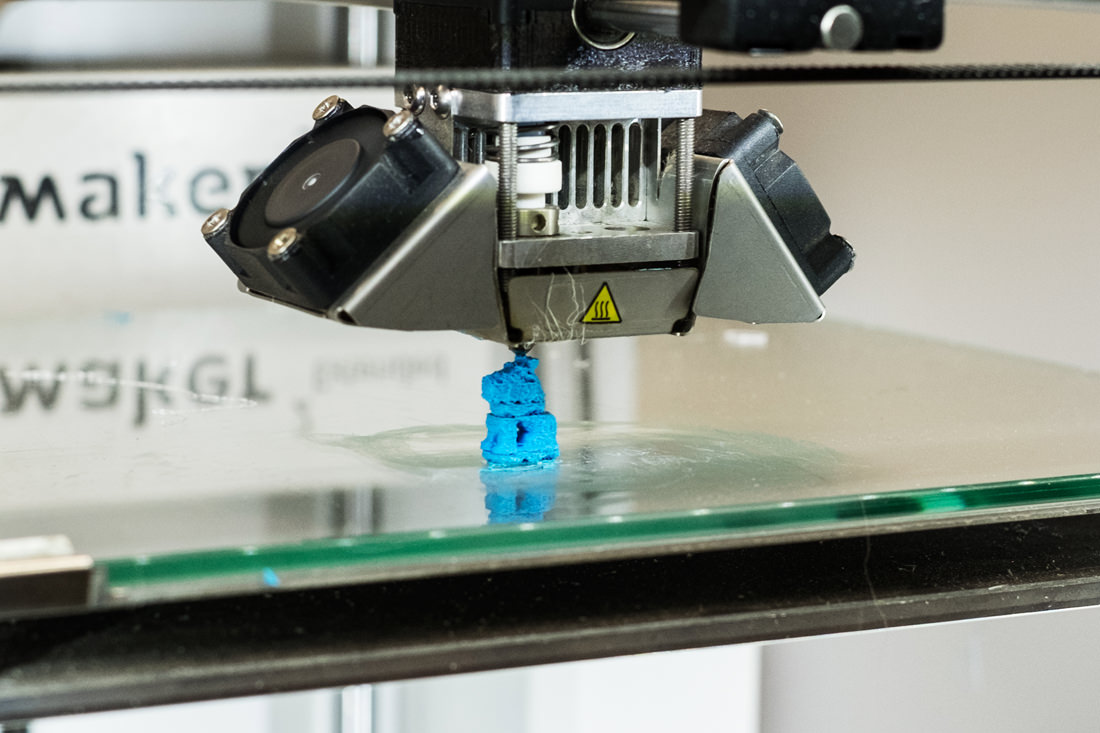

Light Night was the date chosen to launch the exhibition. And, as a special treat, they brought in a 3D printer to print out replicas of the lion statue during the evening.

It was surprisingly fun to watch!

The smallest lions, less than an inch tall, took 30 minutes to print.

I’d brought my two girls along to see the exhibition, and my eldest stood and watched a whole lion print for half an hour. When the machine’s countdown screen got to the last minute, she counted the seconds, and was so excited when it finished, the very nice man looking after the machine let her keep the print.

But, as well as being a bit of fun and entertainment, the prints demonstrate just how close we can get to history and archaeology, but without putting original artefacts at risk. As a university museum, having such accurate replicas like this can be great tools to use with students. They are also a wonderful way to engage your visitors (as my daughters have shown) and, most importantly, they can bring archaeology and history into the hands – literally – of people with visual impairments and other disabilities. The potential for technology to expand the horizons of archaeology is quite exciting.

Further reading

- The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt has a section about Egypt and Nubia’s history, in the chapter ‘Egypt and her neighbours’.

- Wikipedia has articles about Meroë and Nubia

- There are entries for Meroë and Nubia in the British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt

- The Garstang Museum has a blog and an online archive of photographs. They have also created an online gallery of the excavation photographs on Pinterest

- The AcrossBorders research team look at settlement patterns in Egypt and Nubia in the 2nd millennium BC. Although not about Meroë specifically, it’s a really interesting archaeology-based blog to follow

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

[…] enjoyed their Meroe exhibition earlier in the year, and being particularly excited to have been able to spend some time with my […]

[…] The exhibition showed at the Garstang Museum over the summer of 2017. It was held in the museum’s teaching room, used during the academic year, but empty during the summer break. It’s the same room the museum used for their Meroë exhibition in 2016. […]