Photography genesis: a portrait of Hathor

It’s not uncommon for people to find solace in creativity when dealing with difficult times in their lives. For me, photography was what helped me cope during a difficult period in my life. In 2015, I was diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), a disease which leaves me exhausted and unable to do many things I’d previously taken for granted.

I found relief through photography when I started to really explore this art form in the months following my diagnosis. It helped me reframe the world around me, allowed me to live in the moment a little more, and it gave me a sense of purpose and achievement that negated the feeling of hopelessness that comes with ME/CFS.

So in late 2016, I decided to try to bring this new passion together with my other one: Egyptology.

Having enjoyed their Meroë exhibition earlier in the year, and being particularly excited to have been able to spend some time with my camera in the exhibtion, I went to see my friend and curator of the Garstang Museum of Archaeology, Dr Gina Criscenzo Laycock.

The Garstang Museum of Archaeology is the departmental museum for the School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. The university’s where I studied Egyptology, so it’s a place close to my heart.

I asked Gina if I could bring my camera and tripod into the museum galleries and photograph some artefacts as a personal, therapeutic, project. Much to my delight, Gina said yes straight away.

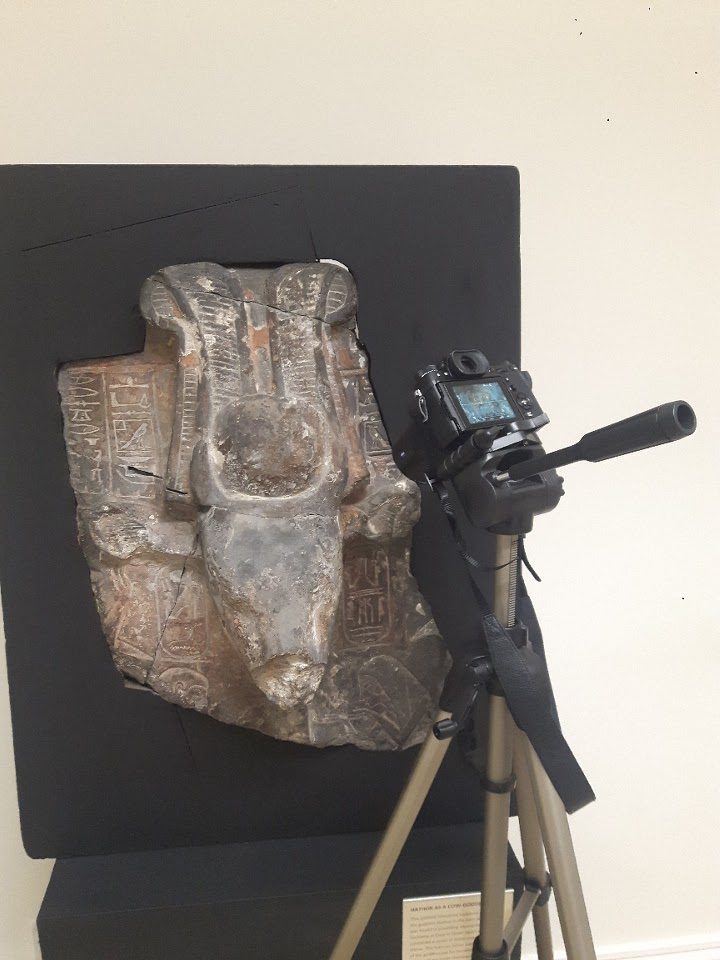

So, back in November 2016, I brought my photography equipment up and plunged straight into working on a statue of the goddess Hathor that anyone who’s visited the museum will immediately recognise.

The statue of Hathor

Reading down the column:

Meretseger, ‘she who loves silence’,

Dehenet Imentet, ‘Peak of the West’

Hwt-Hr

Hwt-Hor

‘Temple of Horus’

A Horus-falcon (Hor) inside the hieroglyph for temple (hwt).

HqA-mAat-ra-stp-n-jmn

Heka-maat-Re Setep-en-Amun

‘Ruler of Maat, like Re, chosen one of Amun’

ra-ms-sw-HqA-mAat-mrj-jmn

Ra-mes-su Heka-Maat Meri-Amun

‘Ramesses, ruler of Maat, beloved of Amun’

This limestone statue of Hathor was excavated by John Garstang in 1906 at Esna, a city around 40 miles south of Luxor. The Egyptian goddess is in her bovine form, which is usually associated with protection of the pharaoh. She’s what’s known as an ‘engaged’ statue, in that she’s a part of a wall, rather than free-standing.

You can still see some of the hieroglyphs from the inscription surrounding her. There are cartouches of Ramesses IV either side of her face, and her own name, Hwt-Hr in Egyptian (hoot-hor), meaning ‘the temple of Horus’, is inscribed either side of her headdress. At the top left, just falling into the broken edge, are the two names of the serpent goddess who protected the necropolis at the Valley of the Kings: Meretseger, ‘she who loves silence’, and Dehenet Imentet, ‘Peak of the West’ (hover/tap on the little ankhs on the photo to get more info. Mobile-device users may need to scroll to the side to see all the text).

Photographing the statue of Hathor

Photographing Hathor in a museum gallery whilst open to the public does, of course, have its limitations. I had no control over the light, and I had to be mindful of other visitors. However, I was extremely lucky that I had permission to bring in a tripod, so I wasn’t having to work handheld.

Swings and roundabouts, I guess.

I started – as is often the case when getting warmed up with a camera – by getting the straightforward, here’s-the-whole-artefact shot you can see in the previous section. It’s not particularly creative or imaginative, but it gets you started and is quite useful to have as a point of reference.

But, once I’d done that, it was time to start having a bit more fun.

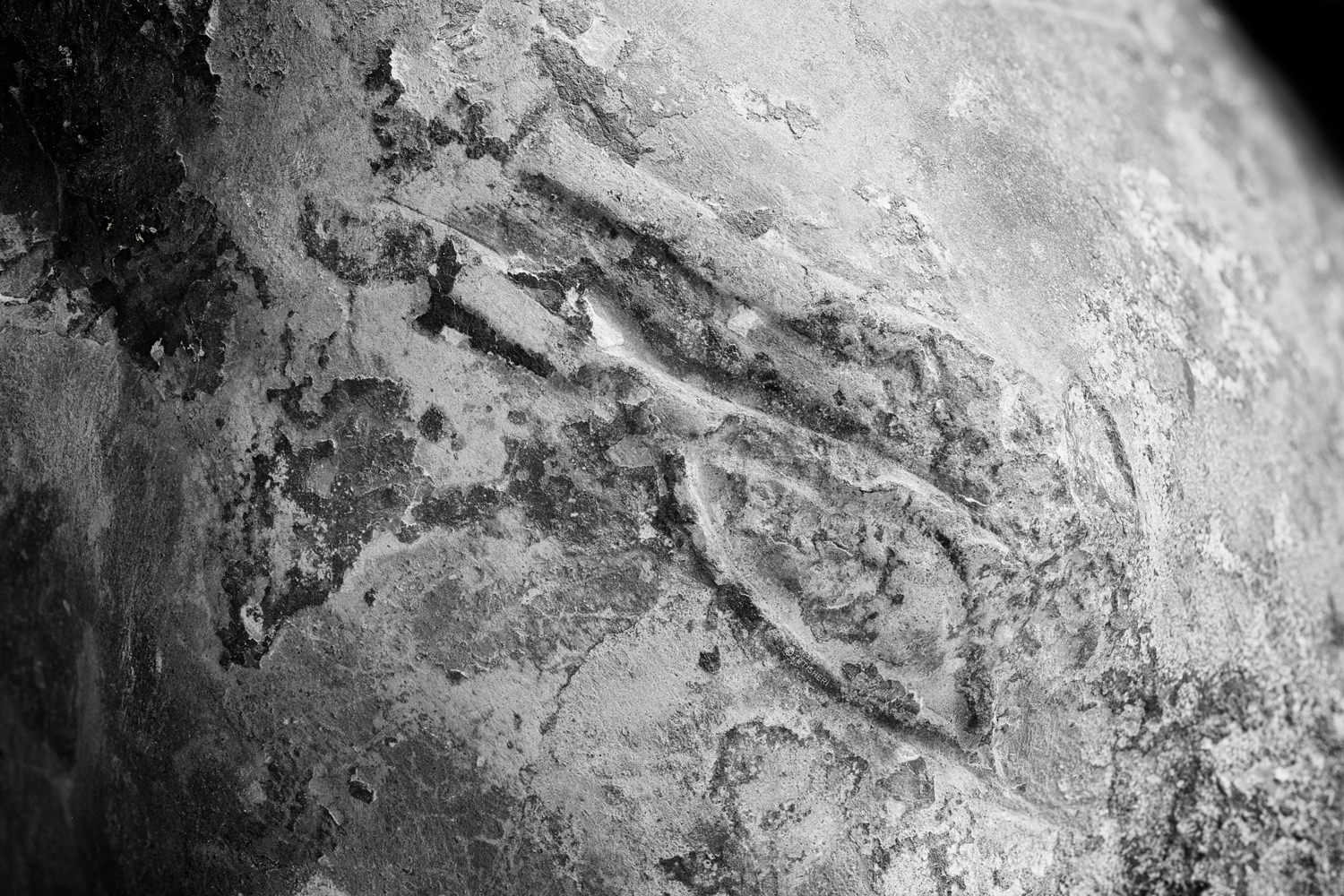

As you can see on that first image, Hathor has sustained some damage over the years, particularly the loss of the end of her muzzle. Also, one of her eyes is more worn down than the other. But the detail that remains is beautiful. So, I moved around to the side with the good eye to get a quarter profile:

I got in closer to focus on just that one eye:

I then moved down to the bottom to photograph that lucky Egyptian receiving a refreshing drink from Hathor at the bottom right corner of the piece.

Firstly, I got right up close into the face to really pick out those fine details:

It then occurred to me that I could have some fun with shallow depth-of-field (where the focus falls away quickly). I moved the camera to the side a little so my camera was at an angle to the surface, and set the focus onto the person’s face:

Then finally, I got right in close to some remnants of gold leaf still on Hathor’s ear.

This is where I had my first real attempt at focus stacking: being this close to an area only a few centimetres wide means focus falls away very quickly, so focus stacking is a must if you want any kind of meaningful image.

It was a bit awkward to get to, partly because I was restricted space-wise, and partly because the gold leaf is on the top of her ear. Plus, I was working with a fairly basic tripod.

However, you work with what you’ve got, don’t you, and this is what I came out with:

(By the way, before you move on, take another look at this last photo. There’s a piece of straw just above the gold leaf. That’s likely leftover from when John Garstang packed her up to bring her back from Egypt. As far as I know, it’s the first time anyone’s noticed it.)

Choosing black and white instead of colour

I decided to use black and white processing for most of these images for one reason; I think they look so much more beautiful than in colour. The statue has such wonderful texture and details, but I found the colour of the surface of the stone a little unappealing. And as this was an exercise in therapeutic creativity, my purpose wasn’t plain documentation of an artefact.

However, I kept the first image in colour, because again, it’s useful as a point of reference.

And the gold leaf … well, the gold is rather the purpose of the image, which would be somewhat lost if I moved to black and white.

What did I learn from this session?

My first and biggest takeaway from this, is that sometimes, if you ask (nicely), you get. I’m sure it helped that I already knew Gina, but she never asked me to prove any kind of photographic capability before she let me in with my camera.

And it was off the back of these photos that she invited me to get involved with the Book of the Dead exhibition. So, yay!

I’ve also learnt that I can use my photography to represent artefacts in my own artistic way. That you don’t have to follow the path of collections database photography. In fact, it’s an awful lot of fun if you don’t!

I learnt that you can use a macro lens to bring a piece to life, and discover details that the naked eye would struggle to see or pass by.

I discovered that working with the textures on the surface of an object can really bring interest into a photo. And when you’re dealing with artefacts that are thousands of years old, damage and wear is a vital part of their story.

What would I do differently?

Nothing’s ever perfect. As well as being new to both macro photography and focus stacking, this was my first exploration into controlled artefact photography. So there are, of course, things that I’d do differently were I to go back do it again.

Which I did actually get the chance to do (yay!). I came up to the Garstang in October 2018 with my camera and tripod and redid a couple of the images; namely, the ones of the eye and the gold leaf.

I focus-stacked the eye and framed it more centrally, so the edge of her eyebrow wasn’t cut off. I did better focus stacking on the gold leaf, and got in closer to it to get greater detail. In the original image, I didn’t do enough focus stacking, so the focus falls away too soon. Not all of the gold leaf is as sharp as I’d like because of it, and the transition from focussed to unfocussed at the bottom of the photo is sudden and a little bit fugly.

Here’s the newer results:

Much better!

However, I still had to be aware of other visitors in the museum, and I was short on time, so it wasn’t, again, ideal. At some point, I’d like to come in on a day the museum’s not open to the public. That way, I could lower the ambient lighting and use my own light to create shadows to bring out the details in the inscriptions and carving.

Of course, ideally ideally, I’d have the statue in a room where I could completely block out all ambient light and have enough space to move around the whole piece.

I’d also like more time to remake images of other details on the statue; the hieroglyphs in particular. I’d made a number of other photos in the original session, but because they were in places where the surface of the object wasn’t flat and I didn’t do focus stacking, the focus is really off. And because I was a bit naughty and didn’t check my images as I was making them, I didn’t even notice until I got my images onto the computer. Rookie mistake!

All-in-all, I had a lot of fun creating these portraits of Hathor. I learnt a lot, and it opened the door for me to become the photographer that stands before you today.

Although there are a number of things I’d do differently, given a second chance, I’m still immensely proud of these photos and how they’ve changed my life for the better.

If you feel the urge to develop your creative photography, whether for health reasons or … well … just because, then do it. It doesn’t have to be big or grand. Start small and simple and see where it takes you. If you need help or collaboration from someone, just ask. The worst that can happen is you get a ‘no’. And if that happens, review your idea, readjust, and keep going.

If you visit the Garstang, try having a go at creating some portraits of Hathor yourself. Try making your own versions of the photos I made, if you like. I don’t mind! Or try your own thing. If you’re not local to Liverpool, find an object that inspires you in your local museum or out and about. Just remember that you can’t waltz into places with a tripod and lights (though you could contact the venue and ask), but I reckon you could get some awesome images even with just a mobile phone in your hand. If you do, please share them with me. I’d love to see them!

[Please note that this is a substantial (read: complete) rewrite and updating of a post I first wrote in February 2017. Because it is such a comprehensive reworking of the original post, I’ve amended the published date to that of the rewrite.]

If you’ve enjoyed these images, this photo is available to buy as a print in my online shop. All purchases help support my work and, in turn, help support the museums I work with.

Shout out to Peter Lundström’s pharaoh.se site for help with the cartouches.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!

Wonderful photographs. Keep going with this. It’s the detail that’s so engrossing.

Thanks, Eleanor! That’s exactly what I was hoping to achieve.

Great stuff, Julia!

If this is a sample of what you intend on the site., I look forward to the rest of your images.

Aw, thanks Jim! I’m looking forward to sharing it with you 🙂