My 5 scariest artefact photography sessions (so far)

I love photographing artefacts. I really do. Not only do I get to explore these beautiful, fascinating pieces from history, it’s a process that is creative, thoughtful, mindful and peaceful.

But, every so often, an artefact comes along that puts the willies right up me.

And no, I’m not talking about photographing mummies in a spooky, Halloween-y way; they’re amazing and awe-inspiring to photograph in their own way, but not scary.

No. What I’m talking about is having to handle and photograph artefacts that are looking for any excuse to start falling apart in your hands.

And, considering I’m photographing objects that are usually at least 2000 years old, I’m surprised this hasn’t happened to me more often.

I’ve done quite a lot of object-handling over the course of my museum-based photography, and will turn my hand to anything, but I really don’t want to be ‘that’ person who hands back an artefact in more pieces than it was given to me. And for that reason I’m ultra careful with my artefact handling.

But sometimes, even the most careful of handling puts an object at risk, and that’s where things get scary.

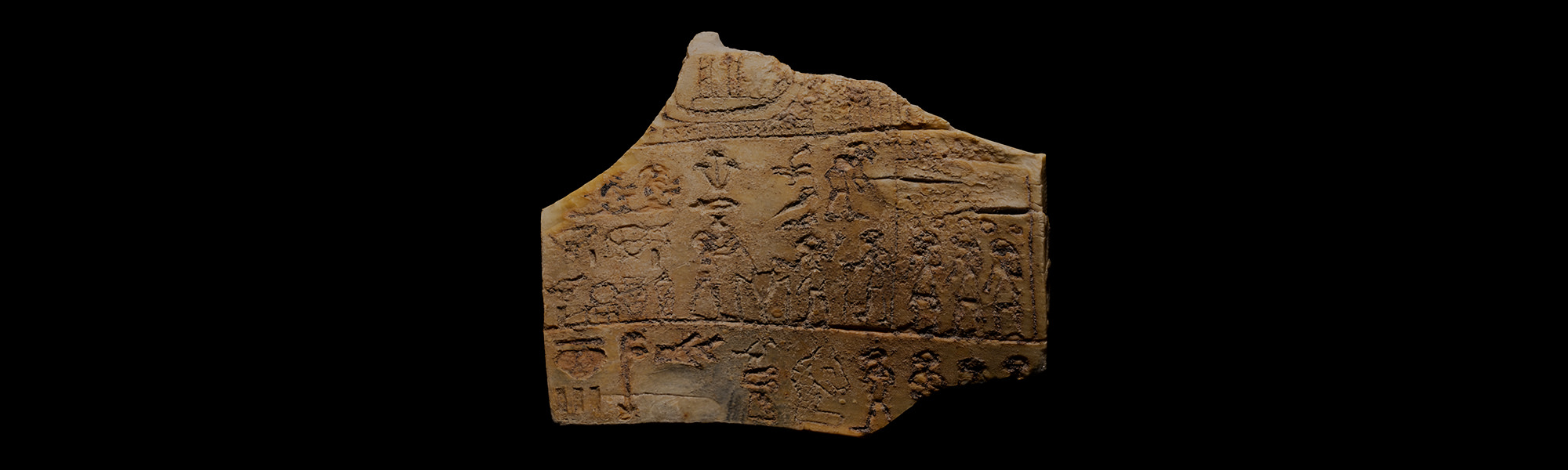

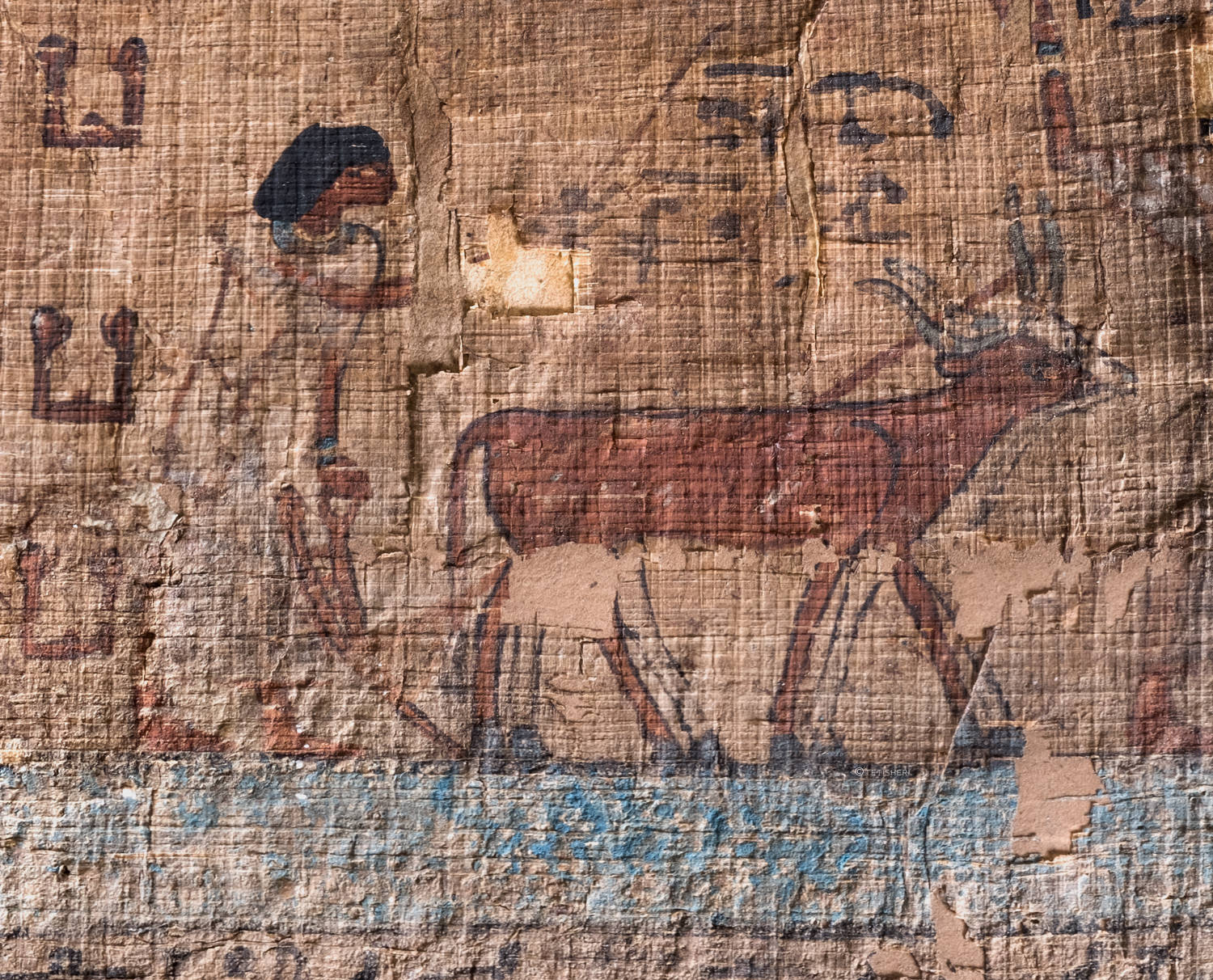

5. A page from the Book of the Dead of Bakenkhons

In the collection at the Garstang Museum of Archaeology is a copy of the Book of the Dead owned by a man called Bakenkhons (‘Servant of Khonsu’), dating to the New Kingdom period (c. 1570–1069 BC).

It consists of several individual pieces of papyrus, with beautiful, colourful illustrations so typical of New Kingdom funerary texts.

Sadly, it’s in a rather sorry state.

At some time in the past, as was not uncommon before the days when conservation was focussed on non-destructive techniques, someone decided to stick the papyrus to sheets of card rather than sandwiching it between panes of glass.

It has also, at some point, suffered water damage.

In the photo above, you can see holes in the papyrus, with the card showing through, and some of the water damage creeping up in the bottom part of the image.

As such, it can’t be kept in the musuem’s usual storerooms, instead being housed in one of the University of Liverpool’s science stores, in temperature- and humidity-controlled conditions.

Because it was too delicate to be exhibited itself in the Garstang’s 2017 Book of the Dead: Passport through the Underworld exhibition, I photographed one of the pages in situ in the science department.

Conditions weren’t ideal. The room was cramped, with white (and therefore reflective) walls and cupboards everywhere. But sometimes, you’ve just gotta do what you’ve gotta do. That doesn’t bother me.

However, at that point, I hadn’t really handled papyrus before, and really, really didn’t want to mishandle this horribly delicate and already damaged papyrus.

So luckily, I had Garstang Museum student volunteer John with me, who did all the physical handling of the papyrus while I photographed it.

To be honest, I’d be quite happy handling this papyrus now myself. With several years’ experience handling artefacts under my belt, I wouldn’t be phased by this. But at the time, I really wasn’t confident doing so, which I was clear about, and so the museum made sure I had someone with me to help out.

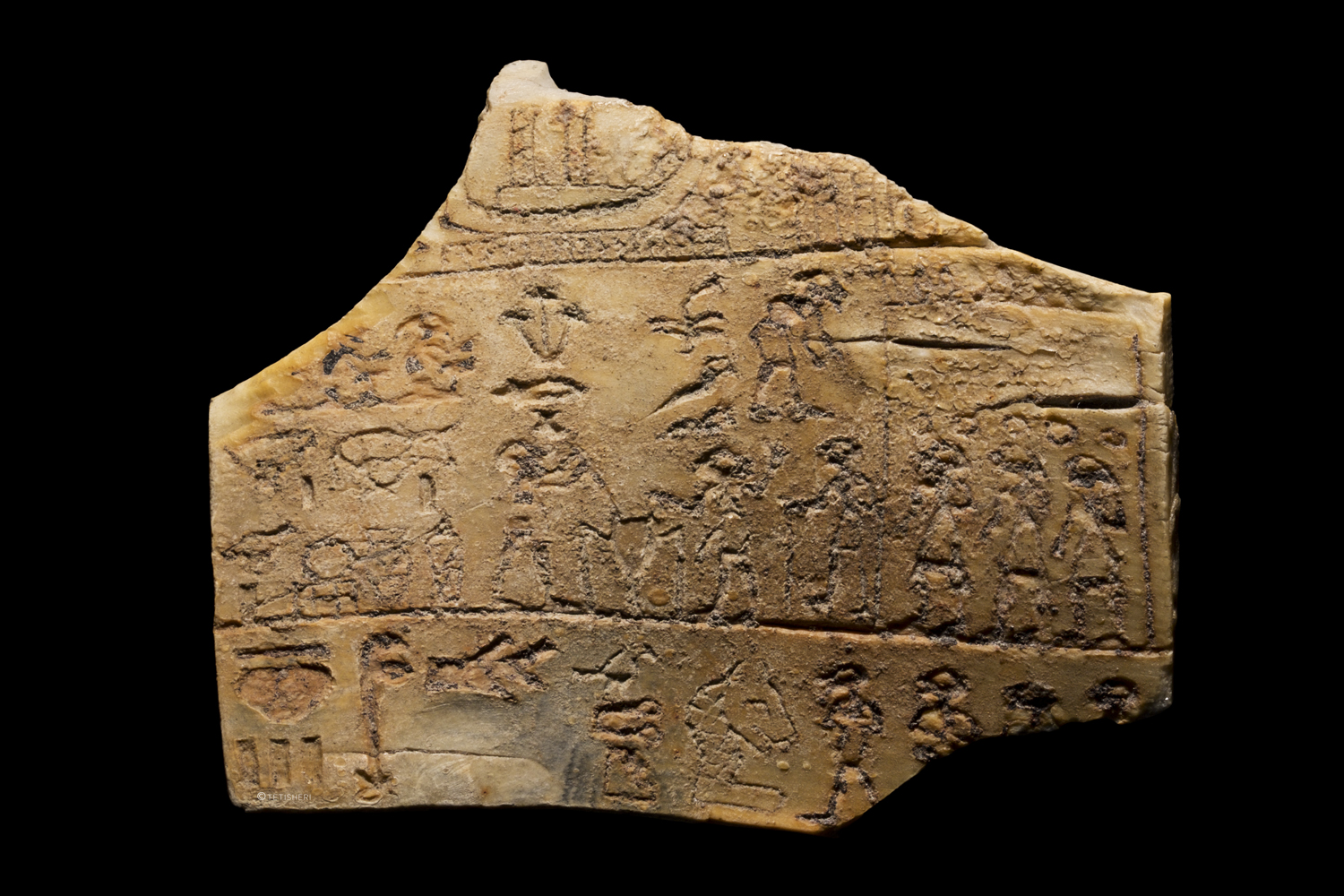

4. An ivory label of Hor-Aha

It may not look like much, but this little piece of ivory is actually quite important.

When writing first emerged in Egypt, it wasn’t as literature, or the complex funerary spells we associate so with the culture.

The earliest writing was on these small ivory and wooden labels that were found attached to storage jars in the graves of the wealthy, and would include the name of the owner.

So yes, in case you’re wondering – the purpose of the earliest writing was to say, ‘This is mine!’

This tiny label I was photographing was found in the royal tomb of Queen Neith-hotep at Naqada. It bears the name of the pharaoh Hor-Aha, one of the first rulers of Egypt, so its inscription is one of the earliest examples of hieroglyphic writing.

And this is why it was scary to photograph.

Not only is the label very small (less than 5 cm across) and thin, making it rather easy for it to slip between your fingers, at 5,000 years old, it’s brittle, too. If it got dropped or knocked, it’s likely to snap. Eek!

So yeah, carefully-does-it was the name of the game.

It’s one of the highlights of the Garstang’s collection and I felt really quite honoured when I got to photograph it for the Before Egypt exhibition. And also kinda glad to be able to hand it back at the end of the session!

3. A Corinthian helmet

Moving on over to Manchester Museum now, I photographed this Corinthian helmet for the Golden Mummies of Egypt exhibition.

If you look carefully, you’ll see it’s cracked in several places, including right across the nose guard (which was held together by a perspex clamp), and is much more delicate than you’d think.

Usually, I’ll just take a trolley or box of artefacts and deal with setting them up myself.

Not this one. I’d have felt more confident handling egg shells.

We asked one of the conservators to come down, who set it up on the table for me to photograph, and removed the clamp from the nose guard.

It was standing on a perspex stand (which I’ve taken out with the rest of the background in Photoshop), which meant I could twizzle it a teeny little bit to get it into the right position. But other than that, I moved the lights and camera instead to get the shot set up, and just didn’t touch it.

2. All the coffins for Golden Mummies of Egypt

I photographed several coffins and mummy covers – including the coffin of the lady Tasheriankh – for the Golden Mummies of Egypt exhibition, and while they weren’t scary to photograph themselves, the way I photographed them was.

Without having a full photography studio and lots of camera rigging to work with, the best way we could come up with to photograph coffins was to hang my camera and tripod out over the edge of the mezzanine in the organics storeroom to look down at the coffins to get those full-length shots.

This involved lashing my tripod securely to the railings on the mezzanine to stop it toppling downwards.

However, it didn’t matter how tightly I secured the tripod; I checked and rechecked and wiggled the tripod several times to make sure it wouldn’t budge, but I was still haunted by visions of it falling onto the coffin, smashing both irreplaceable artefact and camera, and me never being allowed in a museum again …

It didn’t happen, of course. Everything went smoothly and there were no wibbly-wobbly tripod moments. But still … those visions …

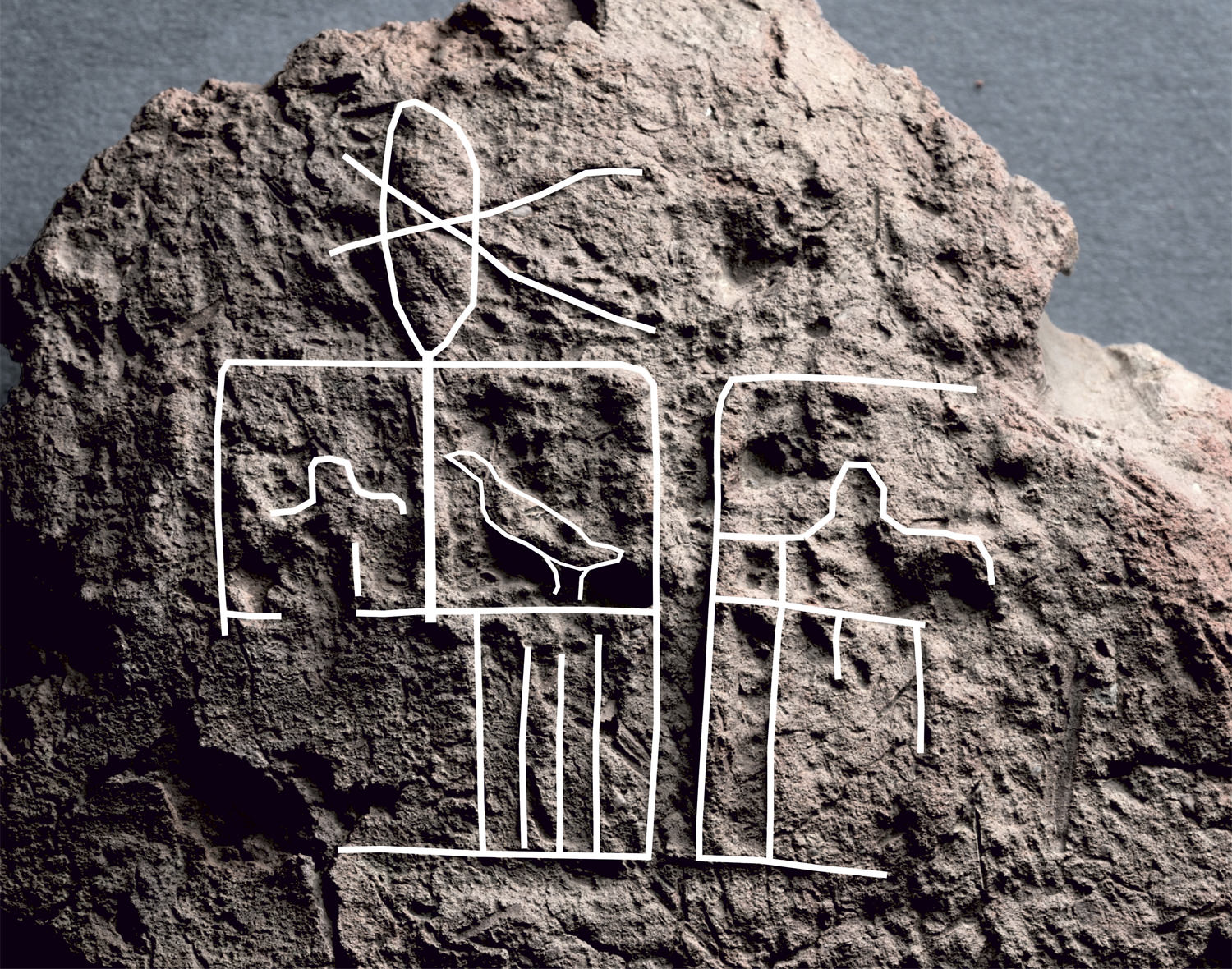

1. A clay seal of Neith-hotep

It’s kinda hard to see what this is, to be honest, and it wasn’t any easier to photograph.

It’s a clay seal with the serekh (a kind of precursor to the cartouche) of Queen Neith-hotep, found in the same tomb as the ivory label above.

The thing is, it’s made out of reeeeeally crumbly, textured, 5,000-year-old clay, which is why it’s hard to make out the hieroglyphs.

And its crumbliness is what made it so scary to handle.

Every time I touched it, bits flaked off.

Every. Time.

Here’s the photo without the background removed. See those bits in the bottom left corner? They fell off when I very gently laid the seal down to photograph.

There was nothing I could do about it. Breathe too heavily, and bits would fall off. Look at it funny, and bits would fall off. It’s not something that was going to get me into trouble though; curator Gina warned me that this would happen. The only thing to do was move it as little as possible, and then gather up the crumbled bits into a small plastic bag afterwards.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering, here’s a photo kindly provided by the Garstang Museum of the seal with outlines showing the serekh:

Still struggling to see it? Yeah, me too …

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!