Sekhmet at the World Museum

Please note: This post was written before the Sekhmet statues were moved up to the Egyptian galleries when they were refurbished and extended in 2017. I will, when I get a moment, update the post in full (and get some better photos!). But, for now, just be aware that the statues are no longer at the base of the stairs.

When you first come into the World Museum in Liverpool, you find yourself in a large, airy foyer with some of the museum’s biggest items on display. This includes an unnervingly large spider-crab shell and a pterodactyl suspended from the ceiling. Here, flanking the entry to the main staircase is a pair of gorgeous Sekhmet statues. Although I was already a little familiar with the ancient Egyptian lioness, I wanted to know more. Who was this enigmatic goddess, seemingly so serene and regal-looking? And what role did she play for the ancient Egyptians? Well, here’s the low-down …

The history of the Sekhmet statues at the World Museum

These statues were a part of Joseph Mayer’s extensive collection of Egyptian antiquities back in the 19th century. Mayer donated the collection in its entirety to the museum in 1867. The statues were, unfortunately, badly damaged when the museum was hit during a bomb raid on the city in 1941. However, apart from the obvious damage you can see in the photos here, they seem to have been really very well restored. If you happen to be in the museum, go and have a peep around the side of the statue on the right. Up at the top, just behind her sundisk, you’ll see the name of a rather famous Italian circus strongman-cum-Egyptologist carved into the stone.

Where do the statues come from?

If you think these statues look familiar, even if you’ve never visited the museum before, that’s because they’re not entirely unique.

They were originally part of a collection of statues installed within the Precinct of Mut at Karnak (see plan below) by Amenhotep III (who also built the precinct itself). They were most likely an attempt to keep this fierce goddess pacified. And what an attempt it was: it’s been estimated that there were over 700 of these statues originally in situ!

The scale of the project is made even more impressive when you consider that the statues were made from diorite; an incredibly hard stone similar to granite, mined in Aswan, in the very south of Egypt.

Mythology

Sekhmet (or Sakhmet, as you may sometimes see it written) became increasingly associated with Mut during the New Kingdom, hence the statues of her in the Precinct of Mut.

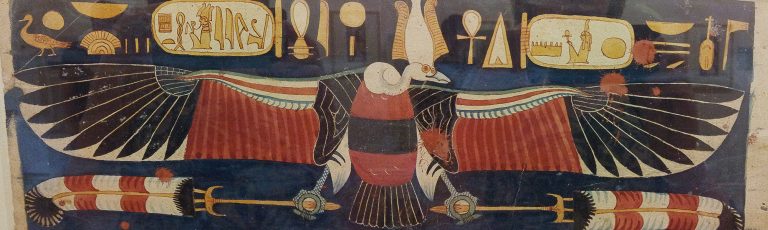

However, her main starring role in Egyptian mythology was in the story The Destruction of Mankind; a New Kingdom tale found in the tombs of Seti I, Ramesses II and Ramesses III, as part of The Book of the Heavenly Cow. Portions of the text are also in the tomb of Ramesses IV and the burial shrines of Tutankhamun.

The story goes something like this:

Back in the mists of time – a mythological, magical time – when people shared the Earth with the gods, Re had been ruling over the land for many years. He was old now; his bones were turning to silver, his skin to gold and his hair to lapis lazuli.

It came to his attention that mankind was plotting against him. So, feeling a little offended by this (as one would!), he called the gods to a secret counsel.

Nun, the god of the primeval waters, advised Re to send down his Eye (seemingly an entity within its own right) to destroy mankind.

Accordingly, Re commanded his Eye, in the form of Hathor, to do the deed. But, as she began, the bloodlust in her arose, and she transformed into the Powerful One, Sekhmet.

Sekhmet rampaged across the land, slaughtering each and every human in her path. No mortal was saved from her bloody revenge.

The day came to an end, the land grew dark, and Sekhmet lay down to rest. As she slept, Re felt remorse for what he had commanded. However, now that Sekhmet had tasted blood, she wouldn’t be easy to stop.

So, Re hatched a plan.

He ordered red ochre to be gathered from the land of Yebu, ground into a powder, and mixed into 7,000 jars of beer. The beer was then poured throughout the fields of Egypt.

When Sekhmet awoke the next morning, she saw the beer and, thinking it blood, began to drink. She drank the whole 7,000 jars and, feeling a little woozy, she returned to Re.

Re retired to the skies, his Eye pacified and mankind thus saved.

If you want to read a translation of the original texts themselves, you can find them in Lichtheim’s Ancient Egyptian Literature Volume II (see bibliography below).

Conclusion

So, in seeming opposition to the serenity of her statues, Sekhmet was a brutal and fearsome goddess, who needed to be kept pacified so she wouldn’t bring death and pestilence to mankind (and as such, she was also a potent healer, able to drive away that which she wrought).

This is probably the reason why Amenhotep III wanted to create such a massive tribute to her in the form of hundreds of statues.

She was also a powerful and violent warrior, who aided the king in battle (for example, Ramesses II’s account of the Battle of Kadesh: Beware, take care, don’t approach him [Ramesses]; Sakhmet the Great is she who is with him, Lichtheim, p 70).

A woman to keep on the right side of, evidently.

Bibliography and further reading

- George Hart, A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses (Routledge, London, 1986), pp 187–189

- Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature Volume II: The New Kingdom (University of California Press, California, 1976), pp 197–199

- Joyce Tyldesley, Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt (Penguin, London, 2010), pp 181–187

- Barbara Watterson, Gods of Ancient Egypt (Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 1996), pp 172–173

- Richard H Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt (Thames & Hudson, London, 2000)

- Egyptology at the World Museum

- Myth of the Heavenly Cow article on eScholarship

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!