Who was Tetisheri?

Warning: this post contains some photos of mummified human remains.

Many years ago, I picked up a copy of a game called ‘Pharaoh’. It was a PC game based on strategic city building that enjoyed a great surge of popularity in the late nineties and early noughties (and still has a few dedicated disciples to this day).

You were given a choice of ancient Egyptian names to use for your character; I immediately fell in love with the name Tetisheri and spent many happy hours playing the game using this name.

I then started using Tetisheri as a username for online forums, games and, eventually, social networking, making her my firmly established online identity. When I put together my website, there was no way I could leave her behind. I’d done a little research into the real Tetisheri in the past, but I decided it’s time to really bring her back to life. So, here she is.

Tetisheri in the historical record

There is very little in the historical record about Tetisheri. There’s a small statuette of her in the collection at the British Museum, but it is, almost certainly, a modern forgery (John Freed, The Finding of Tetisheri’s Statue; John Freed, The (Fake?) Statue of Tetisheri, cont.).

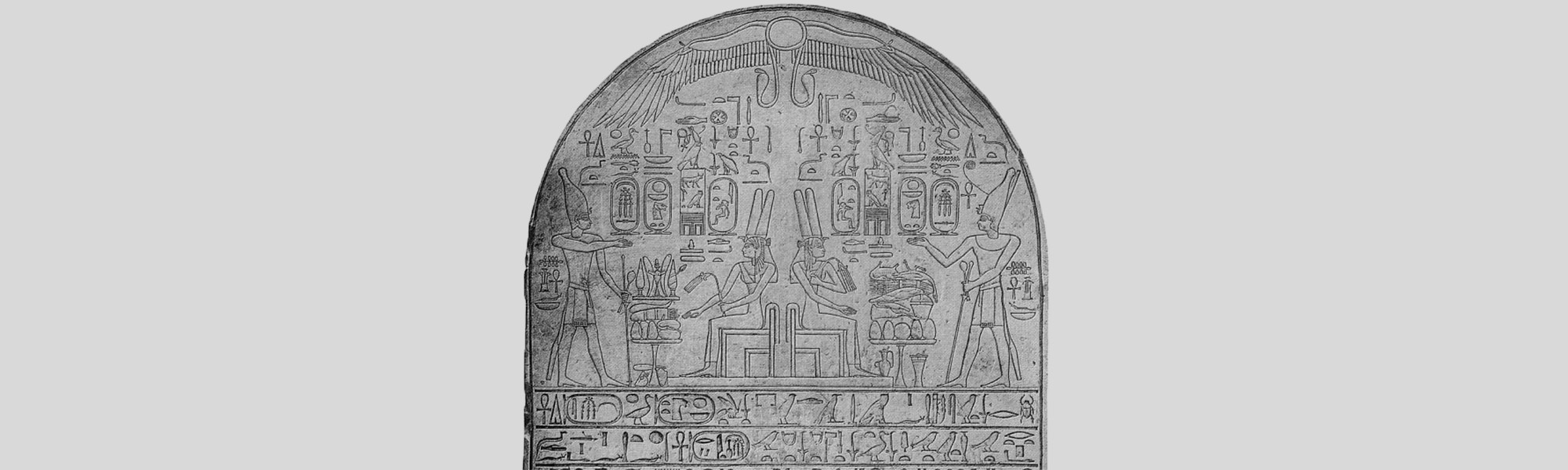

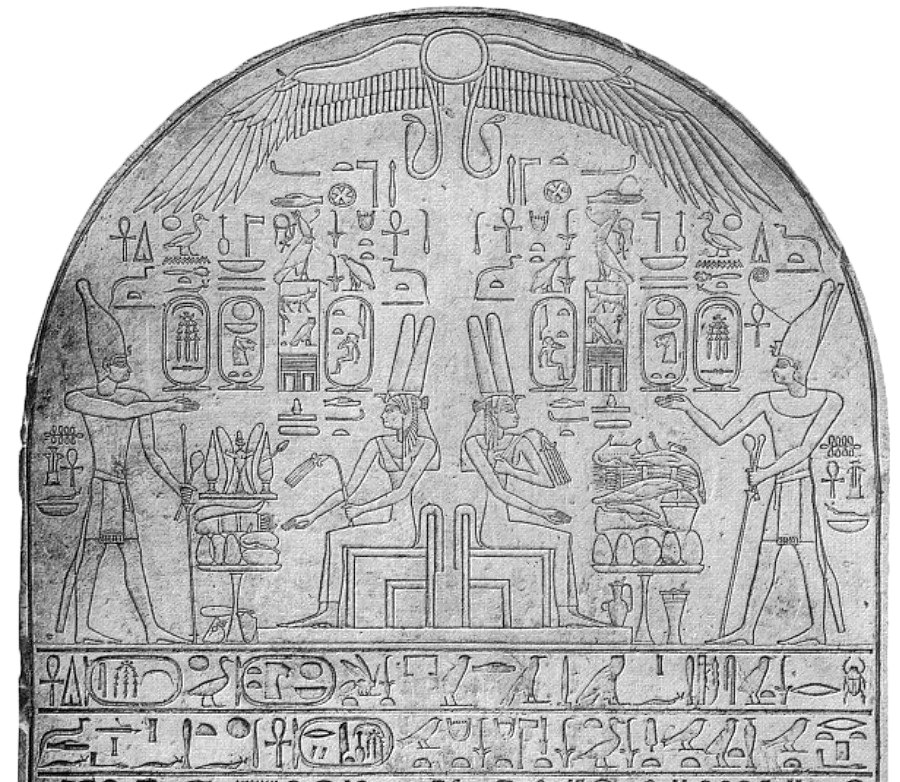

Most importantly, she had a stela dedicated to her by Ahmose I, found in his cenotaph at Abydos.

From this stela, we know that she was Ahmose’s grandmother. He tells us that:

I, it is, who have remembered the mother of my mother and the mother of my father, great king’s-wife and king’s mother Tetisheri, triumphant.

(Translated by Henry James Breasted in Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol II, sections 33–37. For the hieroglyphic inscription, see Kurt Sethe’s Urkunden der 18 Dynastie, pp 26–29.)

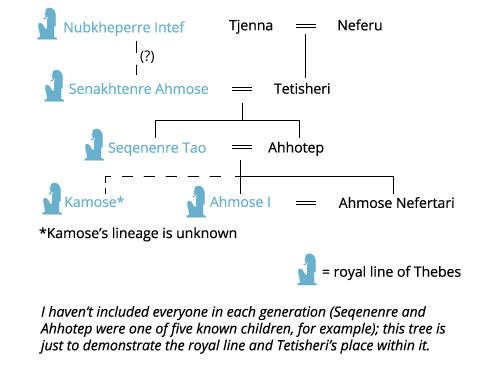

Tetisheri was the wife of Senakhtenre Ahmose, the mother of Seqenenre Taa and Queen Ahhotep, and grandmother of Ahmose I and Queen Ahmose Nefertari (and possibly of Kamose too, although Egyptologists have found it difficult to ascertain Kamose’s position within the Dynasty, and whether he was actually of royal blood at all).

She lived during the tumultuous Second Intermediate Period, but lived to see her grandson Ahmose expel the Hyksos rulers from the north of Egypt and bring royal power back home. In fact, she outlived her own husband and son, and was eventually laid to rest by Ahmose.

Her tomb has not yet been discovered, but she was most likely buried, along with her other 17th-Dynasty counterparts, at Dra Abu el-Naga at Thebes; her stela states that she was buried at Thebes, and her mummy is thought to be that of Unknown Woman B, found in the DB 320 cache (G. Elliot Smith, Catalogue General Antiquites Egyptiennes du Musee du Caire: The Royal Mummies (Le Caire, 1912). Description of mummy, p14; images of the mummy, plates IX and X).

The mummy was found with the name of Tetisheri inscribed on her linen bandages, and is that of an elderly woman, probably around the age of 70. This would fit in well with the fact that she lived through a 30-year war and died in the reign of her grandson. She was a woman of non-royal lineage, and the names of her parents, Tjenna and Neferu, were also written on her funerary wrappings.

Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period

Tetisheri lived towards the end of the Second Intermediate Period – the period marked by the rule of the Hyksos (from the Egyptian name, hekau khasut, ‘rulers of foreign lands’) dating to around 1650–1550 BC.

Political power in Egypt was waning at the end of the Middle Kingdom’s 13th Dynasty, and the Hyksos – migrating from Palestine during the late Middle Kingdom – took advantage of this weakened kingship, and gradually took power for themselves.

They set up their capital at Avaris, modern-day Tell el Dab’a, in the eastern Nile Delta and maintained power from the Delta area down to where upper and lower Egypt meet, around the Hermopolis/Cusae region (despite proclaiming themselves ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt’). They held onto this status quo for about a century.

At the southern end of the country, outside of Hyksos influence, Thebes continued to be the centre of power of Upper Egypt, carrying on from the influence it had enjoyed during the Middle Kingdom. The south of Egypt was ruled firstly by the 16th Dynasty (of which we know very little about; they were likely a collection of minor rulers from various cities in the region) and then the 17th Dynasty.

Unrest between the two centres of power was first documented in a papyrus dating from the reign of Merenptah (approximately 350 years after the war). Apepi, Hyksos ruler, complained that the ‘roaring of the hippopotamus at Thebes [Senakhtenre Taa]’ was stopping him from sleeping. The papyrus ends with Senakhtenre summoning his councillors, presumably to instigate rebellion.

Thus began a 30-year war between the two factions. The Theban rulers built a military settlement at Deir el Ballas, 40 km north of Thebes in which to amass and train their army, which included soldiers from Kerma in modern-day Sudan (although the Hyksos had an alliance with the Kingdom of Kerma, the Theban rulers sacked the fortress town at Buhen, in Kerma, and by Year 3 of Kamose’s reign, the town was back under Theban control. The Kushite soldiers were either forcibly recruited, or volunteered, against the wishes of their own king).

The conflict was not an ongoing, sustained war, however; it was more a series of skirmishes and raids. Although we don’t have details of each and every event, we know that Seqenenre Taa was killed in battle; his mummy shows several nasty wounds, including an axe-chop to his forehead. The shape of this wound is consistent with that of Hyksos war axes.

Kamose, his successor, left an account of what he considered to be a particularly successful raid on Avaris itself. However, it wasn’t mentioned in the biography of Ahmose, Son of Ibana (an admiral of the fleet, serving throughout the war, who left a detailed biography of his career in his tomb) and Avaris wasn’t defeated for a further twenty years, so it’s possible that it was more an exercise in positive propaganda than anything else.

It was Ahmose I who led the final, successful attack on the north, laying siege to Avaris and eventually sacking the city somewhere between Years 18 and 22 of his reign. He continued to campaign as far north as the Lebanon, and south into Nubia, possibly to consolidate his power and his position as Pharaoh. He then spent the last few years of his reign building monuments across the country.

Female power in the late 17th Dynasty

Although our knowledge of Tetisheri is sketchy, I believe she enjoyed greater power than the average Egyptian queen during her family’s rebellion. Whilst inscriptions and dedications to most queens are formulaic and don’t provide much specific information, the queens of the late 17th Dynasty are a different matter.

Tetisheri’s daughter, Queen Ahhotep, was described in a dedication stela at Karnak (from her son, Ahmose) as:

… one who cares for Egypt. She has looked after her [i.e. Egypt’s] soldiers; she has guarded her; she has brought back her fugitives, and collected together her deserters; she has pacified Upper Egypt and expelled her rebels.1

This is quite an exceptional description of a queen. Considering Ahmose’s potentially young age when Kamose died (it was a full 11 years between Kamose’s and Ahmose’s campaigns), it suggests that Ahhotep stood in as regent for her son until he was old enough to take power.

Following on from this powerful queen, Ahmose’s wife, Ahmose Nefertari was not only involved in Ahmose’s building projects, but he even consulted her over the placing of his dedication stela to Tetisheri at Abydos. He also honoured her with a brand new title: God’s Wife of Amun. This new and prestigious position was awarded goods and lands, which remained attached to the office (rather than the person holding it), giving Ahmose Nefertari and her successors considerable wealth and power. She was patron of the workmen’s village at Deir el-Medina on the Theban West Bank, and both she and her son, Amenhotep I, enjoyed cult status, being worshipped by the workmen throughout the New Kingdom.

Conclusion

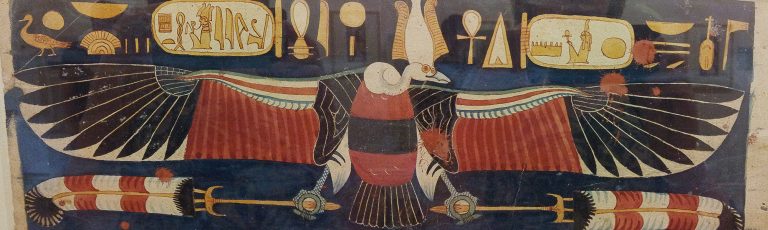

During the Second Intermediate Period, the south of Egypt was isolated; the Hyksos ruled in the north, allied with the Kushites to the south, sandwiching Upper Egypt between them. This isolation is evident in funerary culture: for instance, they had to create their own funerary texts, as they had no access to the scribes at Memphis, thus seeing the emergence of the Book of the Dead in the 16th Dynasty. They also made their coffins out of sycamore, as they were unable to obtain the usual cedarwood, and the quality of these coffins was sporadic and naive.

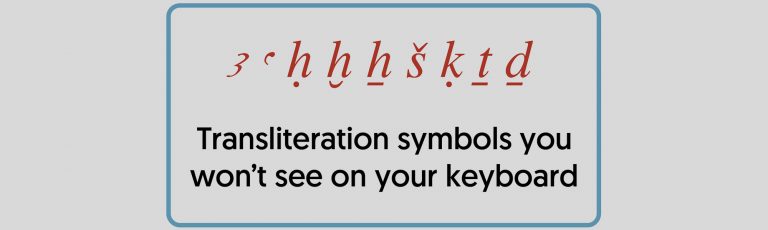

It’s also interesting to note that it was after this time that the Late Egyptian phase of the written language started emerging, replacing the centuries-old Middle Egyptian.

Then when the military settlement at Deir el Ballas was founded, the king of Upper Egypt had to leave his palace at Thebes, and was occupied with the recruitment and training of the army. This must have left an administrative hole at Thebes.

Considering the lack of resources available to the rulers – the men of the family concentrating their energies on the rebellion, the absence of a government to run the country whilst they were away – and the obvious respect in which these women were held by their male counterparts, it’s quite possible that they had stepped into their husband’s administrative shoes and taken over the day-to-day running of Upper Egypt. Tetisheri was granted the honour of having a stela dedicated to her by her grandson, the founder of the 18th Dynasty and a new period of stability and success in Egyptian history, and she was predecessor to two exceptional royal consorts. I don’t think it unfair to consider that she was a strong and capable leader, who set the example on which Ahhotep and Ahmose Nefertari modelled themselves, helping their husbands to oust the invaders and bring the country back under Egyptian rule.

- Gay Robins, Women in Ancient Egypt, pp 42–43 ↩︎

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. If you’ve enjoyed it and would like to support me, you can like/comment, share it on your favourite social media channel, or forward it to a friend.

If you’d like to receive future articles directly to your inbox you can sign up using the link below:

If you feel able to support me financially, you can:

- become a patron of my photography by subscribing for £3.50 a month or £35.00 a year

- gift a subscription to a friend or family member

- or you can tip me by buying me a virtual hot chocolate (I’m not a coffee drinker, but load a hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, and you’ll make me a happy bunny …)

With gratitude and love,

Julia

Unless otherwise credited, all photos in this post are © Julia Thorne. If you’d like to use any of my photos in a lecture, presentation or blog post, please don’t just take them; drop me an email via my contact page. If you share them on social media, please link back to this site or to one of my social media accounts. Thanks!